The Impact Assessment

by EU DisinfoLab Researcher Antoine Grégoire

See the First Branch of the CIB Detection Tree here and the Second Branch here.

Disclaimer

This publication has been made in the framework of the WeVerify project. It reflects the views only of the author(s), and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use, which may be made of the information contained therein.

INTRODUCTION

The coordination of accounts and the use of techniques to publish, promote and spread false content is commonly referred to as “Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour” (CIB). Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour has never been clearly defined and varies from one platform to another. Nathaniel Gleicher, Head of Cybersecurity Policy at Facebook explains it is when “groups of pages or people work together to mislead others about who they are or what they are doing”.[1] This definition moves away from a need to assess whether content is true or false, and whether some activity can be determined as Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour, even when it contains true or authentic content. CIB may involve networks dissimulating the geographical area from where they operate, for ideological reasons or financial motivation. The examples commonly used to demonstrate cases of CIB, and available through the takedown reports published by the platforms, provide insight into what social network activity might be flagged as CIB leading to content and account removal.

What is missing is a clear definition of what CIB signifies for each platform, alongside a wider cross-platform definition, e.g., a clear line of what makes an activity authentic or coordinated and what not.[2] Even though a consensus is emerging on the notion of CIB, the interpretation may vary from one platform to another or between platforms and researchers. This becomes especially important in some context or topics related to politics, such as elections for instance.

Although a clear and widely accepted definition of CIB is currently missing, the concept of malicious account networks, using varying ways of interacting with each other, is observed as central to any attempt to identify CIB. Responding to the growing need for transparency in such identifications, there are several other efforts from researchers and investigators in exposing CIB. The response is at the crossroads of manual investigation and data science. It needs to be supported with the appropriate and useful tools, considering the potential and the capacity of these non-platform-based efforts.

The approach of the EU DisinfoLab is to deliver a set of tools that enable and trigger new research and new investigations, enabling the decentralization of research, and supporting democratisation. We also hope this methodology will help researchers and NGOs to populate their investigations and reports with evidence of CIB. This could improve the communication channels between independent researchers and online platforms to provide a wider and more public knowledge of platforms policies and takedowns around CIB and Information Operations.

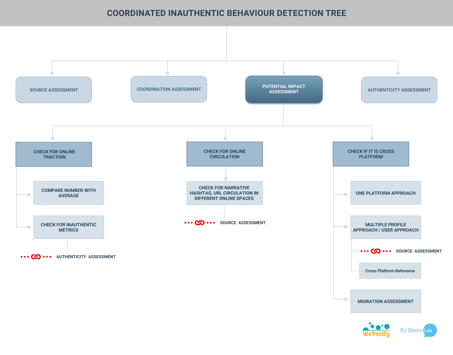

The tools we propose are in the form of a CIB detection tree. It has four main branches that correspond to a series of four blogpost published on our website.

The first branch is the Coordination Assessment[3] and the second branch is the Source Assessment.[4] This is the third branch, the Potential Impact Assessment, using cross platform assessment and metrics to detect CIBs.

The following figure shows the brief overview of the Potential Impact branch.

Online Traction Assessment

Most of the time, one of the first purposes, if not the only purpose, of a CIB network is to increase amplification of content. So looking at content distribution metrics will help to detect or to uncover a possible CIB network.

As a consequence, a useful practice from researchers and Civil Society Organisations is to investigate the metrics of the suspected network’s posts, reach, and engagement or any kind of Key Performance Indicator.

Compare metrics with average figures

Any metric is useful and, once a number has been established, it should be compared with a normal or a reference figure. This will reveal for instance if the network shows numbers that are out of proportion compared to a defined average.

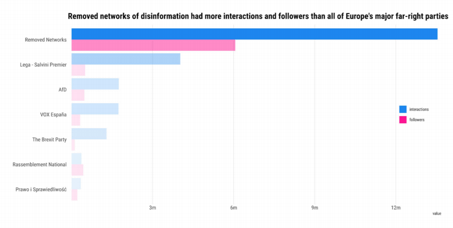

Firstly, Avaaz conducted a study on disinformation on Facebook Pages ahead of the EU elections in 2019. Secondly, the results of the investigation were handled to Facebook, which removed a portion of the pages after its independent investigation. Thirdly, Avaaz then compared the figures of the network removed by Facebook with figures of the official pages of far-right parties in Europe, as the networks removed by Facebook were mostly from Far Right.

“Although interactions is the figure that best illustrates the impact and reach of these networks, comparing the number of followers of the networks taken down reveals an even clearer image. The Facebook networks takedown had almost three times (5.9 million) the number of followers as AfD, VOX, Brexit Party, Rassemblement National and PiS’s main Facebook pages combined (2 million)”[5]

Avaaz used the same criteria to check the metrics of the websites shared by the network they identified. They analysed three media outlets shared by the network and compared the audience reached by these outlets with the numbers one would expect according to their size.

“Political UK25, UK Unity News Network26 and The Daily Brexit. Together, these networks have had 1.17 million followers.”

Then, Avaaz compared the audience reached by these outlets on the social networks to the audience one would expect to encounter, according to their size:

We observed that these “alternative media” all appeared in the top 20 most shared websites in the UK, sometimes above The Guardian and BBC UK, despite being low-authority sites according to independent rankers, with one of these outlets, “The Daily Brexit,” having an ahref[6] domain rating (a metric commonly used to detect spam links) of 0.4 in a scale from 0 to 100.”

The Stanford Internet Observatory Cyber Policy Center in its report “Fighting Like a Lion for Serbia: An Analysis of Government-Linked Influence Operations in Serbia” examined a Twitter takedown report. They noticed that the takedown consisted of 8500 accounts that tweeted 43 million tweets. Among those “2 million tweets were sent with the hashtags #Vucic and #vucic” (which is the name of the president of Serbia in office during the takedown) and “over 8,5 million links to sns.org.rs, informer.rs, alor.rs, and pink.rs, the official site of Vučić’s party and three Vučić-aligned news sites, respectively”[7]

This identifies a massive number of tweets from one sole network using two hashtags and redirecting users to partisan websites. But it is equally important to pay attention to the abnormally low figures, as these can also be indicators of CIBs. The Stanford Observatory notices that “The median account in this network received only four reactions (like, retweet, quote, or reply) in its entire lifetime. Out of 8,558 accounts, 3,244 did not receive a single reaction over the course of their existence.”[8]

Inauthentic Metrics

Checking the inauthentic metrics should be normally part of the Inauthenticity Assessment that will be presented in the fourth blogpost, but inauthentic metrics can easily pop up to the eye when checking at the metrics and assessing the impact in general. While online traction gives more results when it is done on the overall network, inauthentic metrics criteria can be applied to a single account.

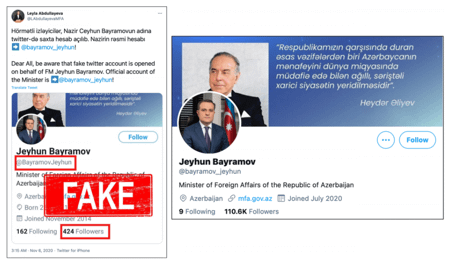

In another analysis of a takedown, the Stanford Observatory[9] shows how the inauthenticity of an account can be quickly deducted using inauthentic metrics criteria, even without reading the content: only 424 followers for a Foreign Minister is not matching the importance of the account and can be considered as Inauthentic Metrics.

When checking inauthentic metrics, the most common observation that can be made are

- A low number of followers compared to a defined average (see figure 2)

- Incoherencies with “likes” and “views”.

Graphika for instance uncovered a network called “Spamouflage Dragon”[10]. When studying the CIB activities of the networks they discovered, some posts or videos had more likes than views, an obvious indicator of inauthentic metrics.

Other inauthentic metrics can also help, for instance a post having more “shares” than “likes” would call for further investigation. While looking at other metrics, it is good to have a look on other incoherent reactions like a post on a disaster that would gather laughs and smiles and check if the profile associated with these inauthentic reactions have other CIB indicators.

- Drastic shrink after a takedown

The drastic shrink of followers can also be a good CIB sign. Especially if this drastic shrink happened at the same time as a major takedown of accounts made by social media platforms.

- Sudden spike or a post performing totally above average

Graphika’s report on Facebook’s Kurdistan takedown uses these criteria as an indicator of CIB. A sudden spike of likes to the pages before reaching a normal line again is observed.[11]

It is also a good indicator if one particular post is performing completely above average.

Inauthentic metrics are also connected to the Inauthenticity Assessment but they will be spotted by looking at other metrics. It is a very good criterion for CIB detection, as CIB is usually designed to manipulate metrics.

Online Circulation Assessment

Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour is most of the time related to elaborated campaigns or designed to support campaigns promoting specific agendas. There is a good chance that these campaigns are elaborated outside the public internet or even offline (in the offices or PR agencies) but have left traces on the internet.

Narratives – Hashtags – URLs circulating in different online spaces

Trying to find these traces and to track back the origin is the purpose of the Source Assessment[12] branch. Therefore, a useful practice is to assess the circulation of the narratives, hashtags or URLs in different online spaces, from a metrics and impact point of view.

This has two advantages, first it will give interesting metrics results that can point to inauthentic metrics as we saw above. Second, because many online tools (SEO, audience measure, advertisement impact) are designed to measure online circulation of links, hashtags or websites.

In a joint study, Rappler and Graphika wanted to measure the impact of a network’s activity and were able to separate the organic activity from the CIB.

“To see how the public responded to the President’s speeches online, Rappler’s data team collected a sample of 15,000 tweets with mentions of Duterte and related words from March 30 to April 2, 2020, and clustered these according to topic using natural language processing”[13]

In this conversation, Graphika assessed that the anti-Duterte activity was organic. They used several criteria. The first one was the diversity of communities that engaged in the anti-Duterte conversations “with the majority of these segments being largely non-political and clustered instead on entertainment and cultural topics. This suggested a wider online dissatisfaction with Duterte beyond the usual online activists,” concludes Graphika.[14]

“The majority of the map showed conversations consisted largely of entertainment and cultural interest segments that lack the density typically observed in politically coordinated accounts”.

Another criterion used by Graphika to establish authenticity was the fact that “about 80% of the accounts that participated in discussion critical of Duterte have more than 100 followers and over 60% of these accounts produced just one tweet using #OustDuterte.”[15]

The number of followers is used to determine the authenticity of the accounts and the one time use of the hashtag is used to determine the authenticity of engagement.

Another criterion was also that the most retweeted tweets originated from “regular” users with a lower number of followers. Such a criterion is interesting but could play both ways. In a CIB activity, the author might want to take advantage of the algorithm and use a highly populated account to issue the first message to ensure maximum visibility and dissemination. However, the EU DisinfoLab, in its study “How two information portals hide their ties to the Russian news agency InfoRos”, uncovered other types of disinformation campaigns where the first source has lower visibility, and the amplifier is the one with the higher audience.[16]

In any case, analysing the context is crucial to use the Metrics Criteria on CIB, to determine comparison points, understand suspect spikes or decrease in numbers, or determine the difference between authenticity and inauthenticity.

Cross-Platform Assessment

The cross-platform criterion can be considered from two different ends. One can adopt a one platform approach or a multiple platform approach.

A single platform approach is more likely what the platforms are doing. They investigate their own field and, if they need to, they go look for hints or intel on the rest of the internet or can do some high-level collaboration. It is a logical starting point for them. On the other hand, a multiple platform approach is what a random social network user would normally do. When thinking of an internet presence, any PR campaign, professional website, or even most basic usage is to think in terms of multiple platforms and creating an account on two or three different platforms, in addition to a website. The single-platform approach is natural for platforms to investigate CIB, while a multiple platform approach is natural for users.

CIB can follow either approach, depending on the planned campaign. Some CIB campaigns prefer to stick to one platform, while others are carrying out their activities on multiple platforms from the beginning. One can start the CIB investigation from any starting point but it is important to adapt to the campaign and to switch or to keep agility between the two approaches.

Single platform approach (starting from one platform to determine CIB presence in other)

In the single platform approach one will start the investigation from a platform and try to check if links to other platforms are displayed.

This is what Graphika did in the study “Inauthentic Reposters”. Graphika started from one Facebook Page and tracked back the campaign on other platforms by following the links displayed by the accounts or pages.

“One of the two Facebook pages, created on May 22, was called Los Optimistas. It did not post any content and only had one follower. Its “About” section listed the Instagram account @longliveblacks under the “website” section. It also listed a gmail address for a user whose Facebook account claimed, on May 29, to have created the @los.optimistas Instagram account.”[17]

It can be useful also to check for outside links to other platforms shared by an account. In EU Disinfolab Report “The Monetization of Disinformation through Amazon: La Verdadera Izquierda”[18] we used Twitter search to look for all Amazon links shared by a specific account. A high number of posts redirecting to monetized links on another platform is a serious indicator of spammy behaviour, that is not taken lightly by the platforms’ CIB policies and can serve as an efficient CIB proof.

Multiple profile approach / user approach

For a multiple platforms approach, one will consider a campaign already operating on different spaces and will check if the same CIB network can be found on different platforms.

It is useful to check:

- If the same usernames are used on different platforms.

- If the same or similar profile picture of an account or set of accounts can be found on different platforms (with the use of reverse image search).

- If the friend lists of accounts in one platform match the follower lists of accounts on another platform.

One will also find cross-platform indicators on the websites shared by the network (see Source Assessment[19]). For instance, many templates used in WordPress already integrate platform sharing buttons. If there is an account, then the link toward the account will appear when hovering the mouse on the button. Sometime two different websites sharing the same Twitter or Pinterest account can reveal they are operated by the same network.

The EU DisinfoLab used that technique to prove how two different Twitter accounts supposedly belonging to two different organisations were redirecting to one another and were operated by the same persons.

Cross platform reference:

It is possible that some networks openly mention cross platform activities. Either in the bio of the account or in some posts, a profile will give the link to its other accounts.

It is a normal activity on the internet and in an effort seeking to maximize online presence, many users enjoy having a profile on different platforms and any professional, organisational, or associated user will follow an online plan involving having a presence on multiple platforms. However, if one has detected a potential CIB on a platform and the profiles of this network openly indicate a multiplatform activity, this could lead to discover CIB activity on another platform.

Thus, one criterion would be to check if there is a cross platform reference, for example, a Twitter account prompting to follow a link to another platform using a text like “go to my VK” or a Telegram account using a text like “go to WhatsApp”. One can also check for URL or links to another platform directly. Looking for “t.me/joinchat” on a Facebook page or a Twitter account might reveal links to telegram channel or groups for instance.

La Verdadera Izquierda report, a combination of cross platform criteria

The EU DisinfoLab report La Verdadera Izquierda[20], describes several instances of cross platform clues and links. Same usernames were used in different platforms, same profile pictures, links to other platform profiles and calls with cross platform reference.

Unboxing & Reviews was created on the 25th March 2019 and it almost exclusively shares videos from a YouTube channel called “Sergarlo90”. Unboxing & Reviews likes a Facebook page called “Ser***Gar*** Lo**” [displaying the full name], and we also found it was connected to a Facebook profile called “Sergio Triatleta”.

On the YouTube channel proposed by Unboxing & Reviews, one could find several clues:

1) Unboxing & Reviews’ website address on Facebook is “Sergarlo90” YouTube Channel and Sergio Triatleta’s Facebook profile has a profile picture of someone using “Sergarlo” as a name on a triathlon competition bib. The person depicted in the photo is the same person that appears in the videos from the Unboxing and Review YouTube channel.

2) The Channel is called “Ser*** Gar*** Lo**”, which is the same name of the public Facebook page.

3) On the right-hand of the YouTube channel, there is a link for the blog “El Rincon de Sergarlo”, which specialises in digital marketing and social network presence and monetisation. El Rincon de Sergarlo is associated with the @Sergarlo Twitter account due to the widget that displays the account’s tweets.

By following the links displayed to the different profiles on different platforms we were able to uncover this CIB network operation running across Facebook, Twitter and Amazon.

Migration Assessment

Together with assessing cross platform impact, there is a specific cross platform activity that can prove useful to assess: the migration.

Migration may happen when a group or page is closed and the people operating the network have to migrate to another group, page or platform. Migration is not necessary an indicator of CIB, as a network composed entirely of CIBs and fake accounts would not have a need to call for migration. But it can be a useful indicator of several things:

- That a network has another activity running on another platform that was overlooked.

- That a network has been impacted by takedown measures or fears to be impacted by counter measures or platform policy.

- That a CIB network has an interest in keeping its real followers.

An internal Facebook report leaked by Buzzfeed shows how Facebook kept an eye for the migration of networks after disabling groups:

We were also able to add friction to the evolution of harmful movements and coordination through Break the Glass measures (BTGs). We soft actioned Groups that users joined en masse after a group was disabled for PP or StS, this allowed us to inject friction at a critical moment to prevent growth of another alternative after PP was designated, when speed was critical.[21]

To have an eye on alternative platforms and user’s possible migration after a ban, takedown or deplatforming will help to understand coordination and networks.

CONCLUSION

The third branch of the CIB detection tree, like the others, was elaborated through careful study of the methodology used by non-platform actors to track CIB and the careful study of the takedown reports and anti-CIB policy used by the platforms. As with any tool involving assessment, OSINT techniques or open-source investigation methodology, entering the world of assessing CIB is entering a world of false positives, misleads and second guessing. This tree is designed to assist researchers and non-platform actors in their investigations. It was designed with automation in mind, part of the tasks described here could be automated or designed to assist human investigations. However, this tool was designed bearing in mind that humans are doing the hard work and only humans can eliminate false positives and misleads.

Although one branch is clearly not enough to properly assess CIB, we do believe that even completed with all four branches the CIB detection tree will be perfectible. We invite you to read our previous blogposts about the Coordination Assessment branch[22] and about the Source Assessment branch[23]. We also believe it will help researchers to populate their report with the language and the examples that the platforms can speak and understand. Because platforms engage themselves in removing and acting against CIB, therefore this tree can be used as a detection tool and as a tool for proving CIB in a particular network already under scrutiny.

[1] https://about.fb.com/news/2018/12/inside-feed-coordinated-inauthentic-behaviour/

[2] https://slate.com/technology/2020/07/coordinated-inauthentic-behavior-facebook-twitter.html

[3] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree1/

[4] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree2/

[5] https://avaazimages.avaaz.org/Avaaz%20Report%20Network%20Deception%2020190522.pdf

[6] ahref.com [is] a well-known SEO tool provider boasting the world’s largest index of live backlinks that is updated with fresh data every 15-30 minutes. “Domain ratings” are a scale (1-100) which illustrate the quality of sites which link back to pages on another site. See /moz.com/learn/seo/domain-authority

https://avaazimages.avaaz.org/Avaaz%20Report%20Network%20Deception%2020190522.pdf p.24

[7] https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu/io/news/april-2020-twitter-takedown

[8] https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/serbia_march_twitter.pdf

[9] https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu/io/news/february-2021-twitter-takedowns

[10] https://public-assets.graphika.com/reports/graphika_report_spamouflage_goes_to_america.pdf

[11] https://public-assets.graphika.com/reports/graphika_report_kurdistan_takedown.pdf

[12] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree2/

[13] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/coronavirus-response-online-outrage-drowns-duterte-propaganda-machine

[14] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/coronavirus-response-online-outrage-drowns-duterte-propaganda-machine

[15] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/coronavirus-response-online-outrage-drowns-duterte-propaganda-machine

[16] https://www.disinfo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/20200615_How-two-information-portals-hide-their-ties-to-the-Russian-Press-Agency-Inforos.pdf

[17] https://public-assets.graphika.com/reports/graphika_report_inauthentic_reposters.pdf p.5

[18] https://www.disinfo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200526_LVI_Final_Word_Version.pdf p.22

[19] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree2/

[20] https://www.disinfo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200526_LVI_Final_Word_Version.pdf p.11 and 12

[21] https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ryanmac/full-facebook-stop-the-steal-internal-report

[22] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree1/

[23] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree2/