The Source assessment

by EU DisinfoLab Researcher Antoine Grégoire

See the First Branch of the CIB Detection Tree here and the Third Branch here.

Disclaimer

This publication has been made in the framework of the WeVerify project. It reflects the views only of the author(s), and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use, which may be made of the information contained therein.

Introduction

The coordination of accounts and the use of techniques to publish, promote and spread false content is commonly referred to as “Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour” (CIB). Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour has never been clearly defined and varies from one platform to another. Nathaniel Gleicher, Head of Cybersecurity Policy at Facebook explains it as when “groups of pages or people work together to mislead others about who they are or what they are doing”.[1] This definition moves away from a need to assess whether content is true or false, and whether some activity can be determined as Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour, even when it contains true or authentic content. CIB may involve networks dissimulating the geographical area from where they operate, for ideological reasons or financial motivation. The examples commonly used to demonstrate cases of CIB, and available through the takedown reports published by the platforms, provide insight into what social network activity might be flagged as CIB leading to content and account removal.

What is missing is a clear definition of what CIB signifies for each platform, alongside a wider cross-platform definition, e.g., a clear line of what makes an activity authentic or coordinated and what not.[2] Even though a consensus is emerging on the notion of CIB, the interpretation may vary from one platform to another or between platforms and researchers. This becomes especially important in some context or topics related to politics, such as elections for instance.

Although a clear and widely accepted definition of CIB is currently missing, the concept of malicious account networks, using varying ways of interacting with each other, is observed as central to any attempt to identify CIB. Responding to the growing need for transparency in such identifications, there are several other efforts from researchers and investigators in exposing CIB. The response is at the crossroads of manual investigation and data science. It needs to be supported with the appropriate and useful tools, considering the potential and the capacity of these non-platform-based efforts.

The approach of the EU DisinfoLab is to deliver a set of tools that enable and trigger new research and new investigations, enabling the decentralization of research, and supporting democratisation. We also hope this methodology will help researchers and NGOs to populate their investigations and reports with evidence of CIB. This could improve the communication channels between independent researchers and online platforms to provide a wider and more public knowledge of platforms policies and takedowns around CIB and Information Operations.

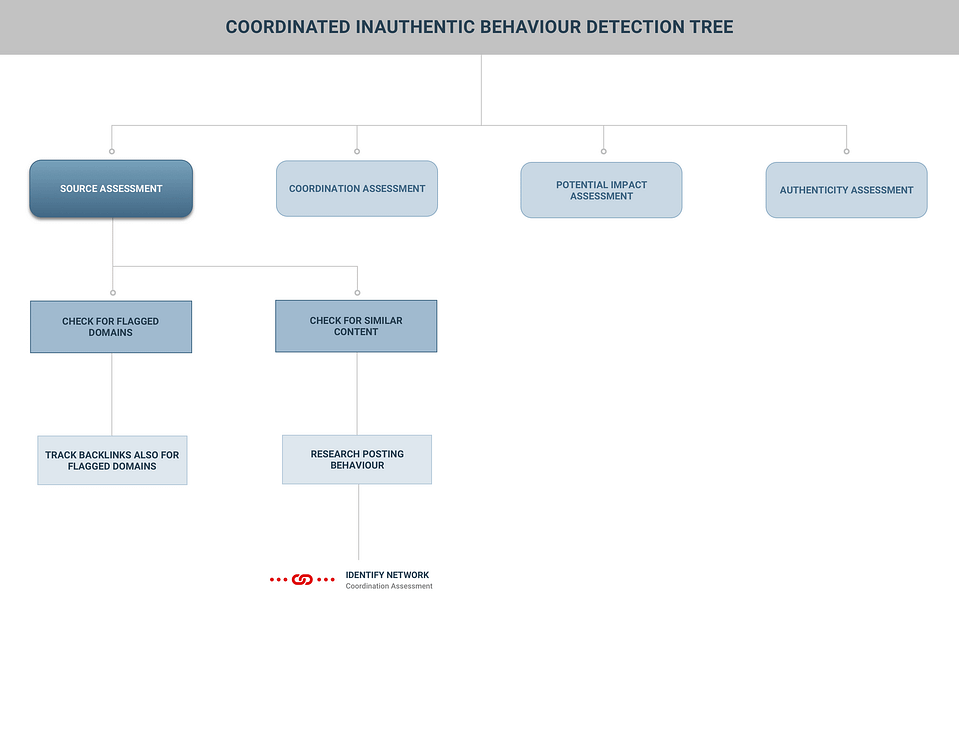

The tools we propose are in the form of a CIB detection tree. It has four main branches that will correspond to a series of four blogpost published in the next months.

The first branch, the Coordination Assessment can be accessed here[3]. This article constitutes the second blogpost: The Source Assessment branch. Or how to track who is coordinating and for what purpose

The following figure shows the brief overview of the Source Assessment branch. (A detailed version of the detection tree can be found in the detection pdf version of the tree.)

Check for previously flagged domains or accounts

One of the main assets for finding Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour will be to determine if the CIBs are part of a network that is already known as inauthentic, or already known for running disinforming or manipulative campaigns. One of the techniques to achieve that is to look closely at what are the domains and website promoted by the suspected CIB network.

Not all CIB involve sharing domain names and website links, but many do. It may happen that these websites have already been flagged as disinformative, hiddenly partisan or are disseminating debunked content.

This can be done by checking if the targeted websites or accounts have already been flagged in a previous archived fact-checking work, or by using open-source data combined, archived, and rendered available by another fact-checking trusted organisation.[4]

External references and archives

Why and how to us references and archives

Any detection or proving of CIB will require reference to previous work on networks, where information of previous CIB campaigns or sources known for disinforming can be retrieved and cross-checked. Archives will also be needed for cross referencing the various profiles or accounts that are coordinating, so any investigation on CIB will involve operating an archive that may or not be kept for subsequent investigations.

As we saw in the previous blogpost, CIB networks are reused and repurposed such as in Graphika’s spamouflage[5] or in the CIB networks investigated by Rappler.[6] In such case archiving the investigation will become useful.

Archives and reference to previous work is also one of the criteria needed to check if CIBs are present across various platforms. Because of the ability to articulate multiple entries, “archive” will be powerful asset to understand cross-platform sharing and operations. How to assess and investigate cross-platform behaviour will be detailed in a subsequent blogpost about the Authenticity Assessment.

Useful open source archived data for CIBs

Many non-platform organisations have their own internal archives. Most fact-checking work involves archiving debunked articles or known websites and some of this work is openly accessible. Le Monde’s fact-checking team “les Décodeurs” has elaborated a fact-checking tool called “Decodex” and made the Decodex database available as an open source resource.[7] WeVerify is currently developing a blockchain project named Database of Known Fakes which will prove useful for detecting and proving CIB activity in association with the CIB detection tree.[8]

Rappler, detecting CIB by detecting links to already fact checked material

A useful practice for assessing the CIB source is to check if the domains shared by the accounts have been flagged in an open-source tool, such as a Database of Known Fakes or a database of known sources of fakes established by a trusted fact-checking organisation like les Décodeurs. It is also useful to check if the domains shared by the network have already been flagged in existing fact-checking exercises or archives.

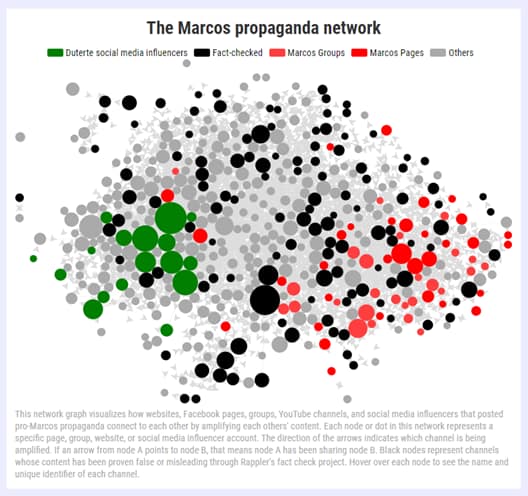

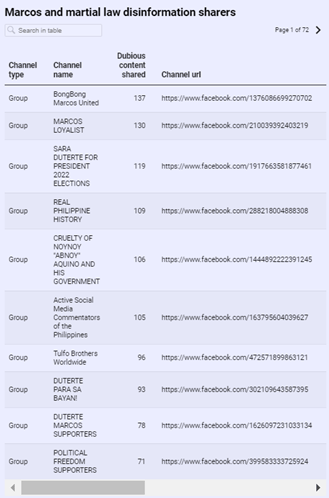

This is how Rappler was able to detect a CIB network used for political propaganda.[9]

Using an archive of debunked claims and fact-checked material, Rappler was able to identify and investigate the groups and accounts that were sharing this material.

Graphika using Twitter “datasets” to detect Spamouflage Dragon network

Twitter, as part of its transparency policy, works on maintaining and making available “datasets” about some of its takedowns and accounts and tweets connected to state operation.[11]

Graphika and the Alliance for Securing Democracy (GMF) created an open and browsable user interface with these datasets.[12] This practice helped them to detect a CIB network they called “Spamouflage Dragon”.

The initial detection was made thanks to Twitter’s transparency policy of “making publicly available archives of Tweets and media that we believe resulted from state linked information operations on our service”. By using this material for content examination and contextualisation, Graphika “uncovered Spamouflage Dragon in September 2019 using signals found in the Twitter dataset, at a time when the network was primarily concerned with attacking two subjects: the Hong Kong protests and exiled Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui, a critic of the Chinese Communist Party”.[13]

Because networks are often reused, repurposed, or resuscitated, checking if accounts have already been flagged in an Information Operation, Disinformation campaign or previously known and archived CIB network, can be crucial and an easy way to detect and prove CIB.

In its study Detecting Digital Fingerprints: Tracing Chinese Disinformation in Taiwan, Graphika detailed how tracking back the accounts sharing material flagged as fake by CoFact fact-checking initiative was instrumental in identifying the source of the disinformation.[14]

Tracking Backlinks

Backlinks are links that are pointing to a specific domain or website. If this website has been identified as being amplified by a CIB campaign, is part of a previous CIB network or has been flagged, it is good practice to track the backlinks pointing to that domain. One must keep in mind that CIBs are not limited to one platform or even to social networks in general.

In its investigation Networked propaganda: How the Marcoses are using social media to reclaim Malacañang[15], Rappler used that criteria to obtain a better delimitation of its network and also for mapping purposes.

Tracking backlinks can be done once the target of amplification has been identified. Tracking backlinks then allows to map the network of the amplifiers. It can also help to identify other websites or pages that are used for amplification, broaden the network of amplifiers and even in some case, by looking at the content, help assessing the intent and motives behind the amplifiers and therefore the source of the CIB campaign.

Similar Content

Checking for similarity in the content of the posts and the material shared by a network is paramount to any CIB study. Sometimes, the exact same content can be found posted multiple times on the internet or on social networks. In that case, it can easily be found by using a simple “exact quote” operator on a search engine. However, for some CIB campaigns, the criteria we are presenting in this branch will be useful to go beyond copy-pasting behaviour.

This branch is intimately linked to the Coordination Assessment[16], as both branches work together. The present branch here describes intends to assess the source of a CIB from the content. However, it is possible to work the other way around, starting from assessing coordination and to examine the content shared by the network. Please check the Coordination Assessment Branch for assessing a Network

In its report “The case of Inauthentic Reposting Activists” [17] Graphika worked on the data from takedown accounts from Facebook. Graphika was able to assess coordination by looking at the similarity of the content: “Sometimes, different accounts in the network posted the same content, or content with very similar messages, at the same time, further suggesting the connection between them.”

If the concept of similar content can be used to assess coordination inside an identified network, it can also be used to detect a network coordination.

Check sequence of hashtags or keywords

The identification of similar sequences of hashtags across messages or posts can become a powerful asset as CIB attempts to hide or obfuscate and avoid detection. Most of CIB campaigns do not use copy-pasting of the exact same message, so they will avoid detection based on the exact same content. However, they might use the same or similar sequence of hashtags. If multiple posts have been identified with this criterion, it is useful to also check the timestamps or timeline of posting to assess more firmly the coordination behaviour.

Identify sequence of hashtags in a dataset for detection

This is a pattern the researcher Raymond Serrato also detected in his study of QAnon posts on Instagram: Using CrowdTangle, I retrieved 166,808 Instagram messages mentioning “QAnon” or “wg1wga” since January 1, 2020. I then extracted the sequence of hashtags used in each message of the dataset and later removed sequences that had not been used more than 20 times. This resulted in hashtag sequences that look like this (the QAnon community isn’t exactly known for its brevity).[18]

The repetition of these sequences helped Ray Serrato to identify some suspicious coordination activities between several Instagram accounts.

Detection and identification of hashtag sequences can be a powerful asset for tracking CIBs. It can avoid monitoring the content to focus only on the behaviour, which is something the Platforms are looking to achieve when they counter CIB[19].

The Centre for Complex Networks and Systems Research, in its study “Uncovering Coordinated Networks on Social Media”, used the detection of hashtag sequences to assess CIB or “Coordinated Networks on Social Media”.

Show hashtag sequence to prove coordination

EU DisinfoLab also used this criterion to assess the CIB in a campaign that was targeting our organisation.

In this instance we see the text and posting is not exactly similar and may vary. The sequence of mentions and hashtags however can show exact similar patterns.

Twitter considers “repeatedly posting identical or nearly identical Tweets” a manipulation of its platform.

Content Pattern

Once a network has been flagged with the help of checking archives, or delimited with the Coordination Assessment, or by any other means, the identification of content patterns is possible. Conversely, identifying content pattern will help tracking back a network of CIB. Identifying content patterns could be particularly useful to extend the research, find accounts that were previously overlooked or navigate the fine difference between Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour and a campaign involving real accounts coordinated to post similar messages.

From an archive of already identified account: check posting behaviour

In its “Detecting Coordination in Disinformation Campaigns”, Raymond Serrato also uses the data released by a Facebook takedown, and a domain tied to a media group known for disinformation as primary criteria to study the behaviour behind the accounts taken down by Facebook who were sharing this domain.

“We’ll look at original data I collected prior to a Facebook takedown of pro-Trump groups associated with “The Beauty of Life” (TheBL) media site, reportedly tied to the Epoch Media Group. The removal of these accounts came with great fanfare in late 2019, in part because some of the accounts used AI-generated photos to populate their profiles. But another behavioral trait of the accounts— and one more visible in digital traces— was their coordinated amplification of URLs to the thebl.com and other assets within the network of accounts.”[20]

This methodology resembles what Rappler and Graphika are doing. But here Raymond Serrato was able to keep the nuance between studying the post content and studying the posting behaviour. Even though it is sometimes not possible for non-platforms to study CIB without studying the content, posting behaviour might be important in the CIB field where the platform insists on keeping Content Moderation away from Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour. Studying the posting behaviour of an identified network helps to identify the goal and to assess the source of the CIB, its intent and purpose.

Turning Point: CIB campaign from humans paid to use their own accounts

One of the main criteria for some platforms for detecting and removing CIBs is based on the presence of “Fake Accounts”. It is not the case for every platform, but it is one of the main criteria for Facebook, for instance.[21]

However, it may happen that a CIB is operated with humans paid to use their own accounts. In such case, the Similar Content Pattern criteria becomes an asset to detect and to prove CIB operation.

Such was the case with the removal of a campaign launched by US conservative group Turning Point. The Washington Post did an investigation on this campaign, using the identical or similar content as a criterion for both detection and as a proof of manipulation. Here are some of their key findings[22] and how this can be used to detect and assess CIBs, all quotes come from the Washington Post article:

- Similar Message made possible the identification of “spam-like behaviour” campaign operated by humans.

“The campaign draws on the spam-like behaviour of bots and trolls, with the same or similar language posted repeatedly across social media. But it is carried out, at least in part, by humans paid to use their own accounts.”

- Identical content allowed the constitution of a dataset to analyse and investigate

“Nearly 4,500 tweets containing identical content that were identified in the analysis probably represent a fraction of the overall output.”

- Careful look at parcelling and incrementation of the messages can be used to assess or prove high level coordination

“The messages — some of them false and some simply partisan — were parceled out in precise increments as directed by the effort’s leaders, according to the people with knowledge of the highly coordinated activity.”

- Traces of content patterns can be found in highly elaborated CIB campaigns, even with high level techniques designed to avoid detection.

“Those recruited to participate in the campaign were lifting the language from a shared online document, according to Noonan and other people familiar with the setup. They posted the same lines a limited number of times to avoid automated detection by the technology companies, these people said. They also were instructed to edit the beginning and ending of each snippet to differentiate the posts slightly, according to the notes from the recorded conversation with a participant.”

Identifying the Similar Content Pattern, lifted from a shared online document, was instrumental in detecting and proving CIB. Facebook and Twitter then acted on the Washington Post report and removed some of the accounts.

Conclusion

The second branch of the CIB detection tree was elaborated through careful study of the methodology used by non-platform actors to track CIB and the careful study of the takedown reports and anti-CIB policy used by the platforms. As with any tool involving assessment, OSINT techniques or open-source investigation methodology, entering the world of assessing CIB is entering a world of false positive, misleads and second guessing. This tree is designed to assist researchers and non-platform actors in their investigations. It was designed with automation in mind, part of the tasks described here could be automated or designed to assist human investigations. However, this tool was designed bearing in mind that humans are doing the hard work and only humans can eliminate false positives and misleads. This will be even more the case with automation applied to archives.

Archives can be manually populated, or crowd-source populated, like in the case of CoFact[23], or with the help of some automation. Automated data collection can also quickly become a problem. Researcher Evelyn Douek reminds us how the platforms were able to collaborate and to agree to ban Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM). Despite CSAM being a precise and definable category, the automation of this database caused the blocking of Scorpion rock band Wikipedia page because of one of the band album cover[24].

Although one branch is clearly not enough to properly assess CIB and two more are to come, we do believe that even completed with all four branches the CIB detection tree will be perfectible. We invite you to read our previous blogpost about the Coordination Assessment Branch[25]. We also believe it will help researchers to populate their report with a language and example that the platforms can speak and understand. Because platforms engaged themselves in removing and acting against CIB, therefore this tree can be used as a detection tool and as a tool for proving CIB in a particular network already under scrutiny.

[1] https://about.fb.com/news/2018/12/inside-feed-coordinated-inauthentic-behaviour/

[2] https://slate.com/technology/2020/07/coordinated-inauthentic-behavior-facebook-twitter.html

[3] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree/

[4] Le Monde Decodex Database https://www.lemonde.fr/webservice/decodex/updates; GMF-Graphika’s IO https://www.io-archive.org/#/; CoFact platform https://blog.cofact.org/collaborative-fact-checking/

[5] https://graphika.com/reports/return-of-the-spamouflage-dragon-1/

[6] https://r3.rappler.com/move-ph/plus/252085-members-briefing-marcos-networked-propaganda

[7] https://www.lemonde.fr/webservice/decodex/updates

[8] https://weverify.eu/about-us/overview/#1560343088338-24c0bae8-7ae8

[9] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/investigative/marcos-networked-propaganda-social-media

[10] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/investigative/networked-propaganda-how-the-marcoses-are-rewriting-history

[11] https://transparency.twitter.com/en/reports/information-operations.html

[12] https://www.io-archive.org/#/

[13] https://public-assets.graphika.com/reports/graphika_report_spamouflage_goes_to_america.pdf, p. 2.

[14] In late 2019, The Reporter traced several large content farm networks back to Evan Lee, a businessman in Malaysia who allows users to create their own content and websites through his content farm “platform.” The operator of one of these smaller networks, GhostIsland News, claimed that Evan Lee’s nationality was Chinese. When The Reporter asked Lee about his nationality, he responded that it was a secret (J. H. C. Liu et al., 2019). Many domains from this network are known to disseminate disinformation in Taiwan; nine separate domains belonging to Lee’s network appeared in the Cofacts public database of debunked disinformation stories, representing 37 separate false stories.

[15] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/investigative/marcos-networked-propaganda-social-media

[16] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree/

[17] https://public-assets.graphika.com/reports/graphika_report_inauthentic_reposters.pdf p.6

[18] https://medium.com/swlh/detecting-coordination-in-disinformation-campaigns-7e9fa4ca44f3

[19] See the video of Nathan Gleicher “Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour Explained”, https://about.fb.com/news/2018/12/inside-feed-coordinated-inauthentic-behavior/

[20] https://medium.com/swlh/detecting-coordination-in-disinformation-campaigns-7e9fa4ca44f3

[21] “We view CIB as coordinated efforts to manipulate public debate for a strategic goal where fake accounts are central to the operation.” Introduction to Facebook February 2021 Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour Report https://about.fb.com/news/2021/03/february-2021-coordinated-inauthentic-behavior-report/

[22] https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/turning-point-teens-disinformation-trump/2020/09/15/c84091ae-f20a-11ea-b796-2dd09962649c_story.html

[23] https://blog.cofact.org/collaborative-fact-checking/

[24] Despite CSAM being a relatively definable category of content, there can still be unexpected collateral damage without adequate procedural checks. The mistaken addition of the album art for the Scorpionsalbum Virgin Killer by the IWF to its Child Abuse Imagery Database in 2008 not only caused ISPs to block access to the band’s Wikipedia entry but also prevented most U.K. web users from editing the entire Wikipedia domain, for example. https://knightcolumbia.org/content/the-rise-of-content-cartels

[25] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/cib-detection-tree/