By Trisha Meyer, Alexandre Alaphilippe and Claire Pershan

In this article, we map, compare and analyse the monthly COVID-19 disinformation monitoring reports that platforms have submitted to the European Commission as part of their commitment to the Fighting COVID-19 Disinformation Monitoring Programme. This monitoring and reporting programme was established from the 2020 Joint Communication “Tackling COVID-19 disinformation – Getting the facts right” to ensure transparency and accountability among platforms and industry signatories to the Code and to mitigate the spread of Covid-19 related disinformation online. For additional assessment of the effectiveness of this reporting programme, see our publication from February: “One Year Onward: Platform Responses to COVID-19 and US Elections Disinformation in Review”. Here, in an effort to assess the commitments of platform signatories towards member states, we focus on the references in the reports to country-level actions to address COVID-19 related disinformation.

Before we get started – we need to get one thing off our chests: the platforms’ monthly reports are annoyingly diverse. They broadly follow platforms’ commitments to the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation, but each platform has their own reporting style and fills in the metrics according to their preferences, and none provides much granular country-level data. The reports thus only become comparable with significant effort. The reports themselves are also not easy to find. The best place to locate the monthly reports on the European Commission website is here.

Having said that, here it is!

491 pages of monthly COVID-19 disinformation monitoring reports from Facebook, Google, TikTok and Twitter, dated from August 2020 to March 20211, squeezed into 2 colourful timelines and 1 article. You are welcome.

Summary

- Our four take-aways are:

- Platform country-level responses focus on prioritizing and amplifying credible content through information displays and free advertising space.

- Platform country-level responses also focus, but to a lesser extent, on media literacy campaigns and fact-checking partnerships.

- Platform responses that limit the spread of content or accounts are not country specific.

- A handful of big member states are prioritised while others are neglected.

- Our three action points are:

- Harmonise the reporting. This should include an obligation to clearly highlight new actions in order to facilitate analysis and transparency.

- Require signatories to provide country-specific metrics, especially regarding the audience of disinformation, engagement (clickthrough rate, etc.), funding of in-country fact-checking or research activities, and indicators of the prevalence and strength of in-country civil society relationships.

- Establish a register of beneficiaries of ad-credits detailing amounts granted, spent, as well as report on the impact of these policies.

This article is most useful when considered alongside our first analysis published in February, which reviewed platform responses to COVID-19 and US election disinformation in 2020, regardless of location. Indeed, as we will notice, the vast majority of the platforms’ disinformation actions are not country specific.

Similar to our first analysis, the entries in these timelines are beautifully colour-coded (by month) and there are two tabs (platform-country and response-country). You can zoom in/out depending on how micro/macro of a view you want. You can access the timelines here by platform and response type (two tabs).

It is important to stress that we only map what the platforms report. Other country-level action might well be taking place, but then it hasn’t made its way into these monthly reports (yet)2.

So what does the country-level mapping of platform responses to COVID-19 related disinformation reveal?

Take-away 1: platform country-level responses focus on prioritizing & amplifying credible content through information displays and free advertising space.

Platforms were quick to set up COVID-19 related information displays, information centres and search prompts. They also made extensive free advertising credit available for governments, public health authorities and non-profits to promote public health information and run public awareness campaigns.

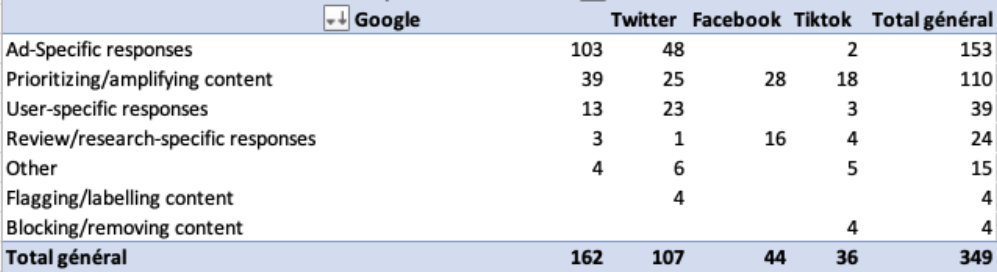

according to action type

With the exception of Twitter, however, there is little country-level information available in the reports on who makes use of the free advertising credits.

- In August 2020, Facebook reported that there are country-level information displays available in all EU member states, with the exception of Malta and Poland. Their COVID-19 information centres are available in all member states.

- Facebook has not provided country-level reporting on advertising credits. In August 2020, Facebook indicated that they had made more than $30M in ad coupons available for ministries of health and similar organisations in 128 countries.

- Google developed a COVID-19 section on Google News in 12 EU member states and provides a list of authorised vaccines in Google Search in all EU member states.

- Google has not provided country-level reporting on advertising credits. In August 2020, Google indicated that they had more than $250M available in ad grants to help the World Health Organisation and more than 100 global government agencies, of which $50M ad grants to EU governments and public authorities; and also $76M to EU-based nonprofits.

- TikTok supported country-level public awareness campaigns and applied the sticker ‘Learn the facts about COVID-19’ in 9 member states.

- In August 2020, TikTok reported that they had provided free advertising space to the French government and Irish Health Service, and that they granted $25M in prominent in-feed ad space to NGOs, trusted health sources, and local authorities.

- Twitter provides country-level information on search prompts, promoted trends and vaccine prompts for 17 of the 27 member states.

- Twitter’s monthly reports include country-level and actor-specific reporting on use of ‘Ads for Good’. So far, they have been used in 12 of 27 Member States. In August 2020, Twitter noted that ‘Ads for Good’ were offered to all EU Member States.

Take-away 2: platform country-level responses also focus, but to a lesser extent, on media literacy campaigns and fact-checking partnerships.

Platforms run media literacy campaigns in select EU member states, with the exception of Facebook who ran a global campaign in multiple languages in all EU member states. Google and Twitter do not provide details in the reports on their fact-checking partnerships; Facebook only cites the amount of partnerships; Tiktok has fact-checking partnerships in three EU member states.

Platform information on financing of fact-checking will be detailed separately under take-away 4.

- In August 2020, Facebook reported that they launched a digital literacy programme “Get Digital in English”, with expansions into French, German, Portuguese, Italian and Spanish planned. In September 2020, Facebook highlighted their digital literacy campaign to stamp out fake news, available in 56 countries (including all 27 EU member states) and 27 languages. The media literacy campaigns that were country-specific related to upcoming elections in the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania and Spain.

- Most recently, in February 2021, Facebook reported 35 fact-checking partnerships in Europe, covering 26 languages.

- Google developed education and prevention websites in 9 member states; ran or supported media literacy campaigns in 4 member states (Czech Republic, France, Germany and Spain); and provided News Lab Training for journalists in Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese and Spanish. In December 2020, Google funded the creation of a COVID-19 Vaccine Media Hub, globally, with content available in 7 languages.

- Google does not report in which EU member states that they have fact-checking partnerships.

- In November 2020, TikTok reported on Project Halo (UN and Vaccine Confidence Project), which is available in English, Portuguese and Arabic. In December 2020, Project Halo onboarded doctors and researchers in France, Italy and Spain.

- TikTok fact-checks in English, Spanish, French, Italian and German, and reports having fact-checking partnerships in 3 EU member states (France, Italy, Spain).

- Twitter reports on media literacy training in 13 member states. For instance, in March 2021, Twitter’s Youth Summit on media literacy and digital citizenship brought together young people from Austria, Belgium, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Portugal.

- Twitter does not report in which EU member states that they have fact-checking partnerships.

Take-away 3: platform responses that limit the spread of content or accounts are not country-specific.

Many of the more invasive platform responses (flagging & labelling, blocking & removing, limiting & demoting, account-specific) are not country-bound, but flow from platform community rules and guidelines. While this makes sense because these platform guidelines are universal, it shows how there is not much country-based tweaking/adapting going on – or at least not that platforms are putting in their monthly reports.

On these points, we refer back to our first analysis. Below we summarise what is country (or language) specific.

- Facebook gives some indication of languages covered for flagging & labelling and blocking & removing.

- In particular, in August 2020, Facebook reported that pop-ups on disinformation redirecting to WHO are available across all EU member states, in Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Slovene, Spanish and Swedish.

- In August 2020, Facebook shared news about improvements to proactive detection technology and expanded automation in English, Spanish, Arabic, Indonesian, Burmese; in March 2021 they indicated that updates in technology were made in Arabic, Spanish and Portuguese (for hate speech) and improvements to proactive detection and removal on bullying and harassment in English on Facebook and Instagram.

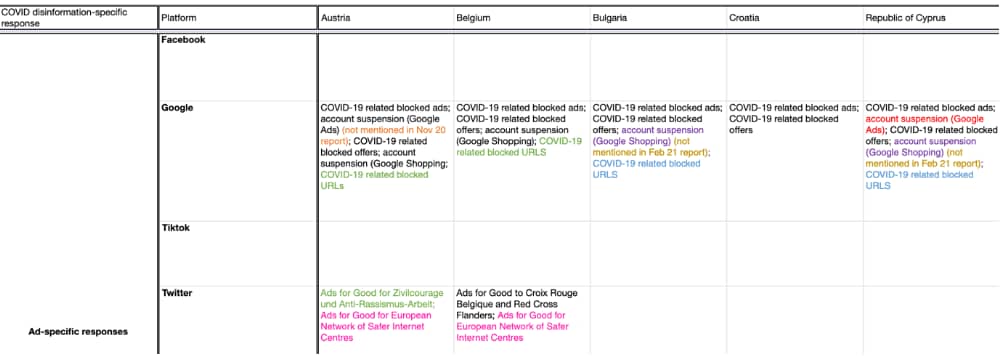

- Google’s monthly reports include country-level reporting on COVID-19 related blocked ads and offers, URLs and account suspensions.

- TikTok provides some information on blocking & removing on a country-level basis. In September 2020, TikTok reported that they removed videos (in violation with the terms Coronavirus or Covid, medical misinformation) in France, Germany, Italy and Spain (their “four biggest markets”). As of February 2021, they are able to provide data for the “all-EU” region, including those four member states.

- In September 2020, Twitter started labelling government accounts from the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. Within the EU, this includes France. In March 2021, they reported expansion of this labelling to an additional 16 countries worldwide. Within the EU, this includes Germany, Italy and Spain.

Take-away 4: a handful of big member states are prioritised while others are neglected.

The dominance of some member states might have already become noticeable when reading the first three take-aways, but it is well worth elaborating.

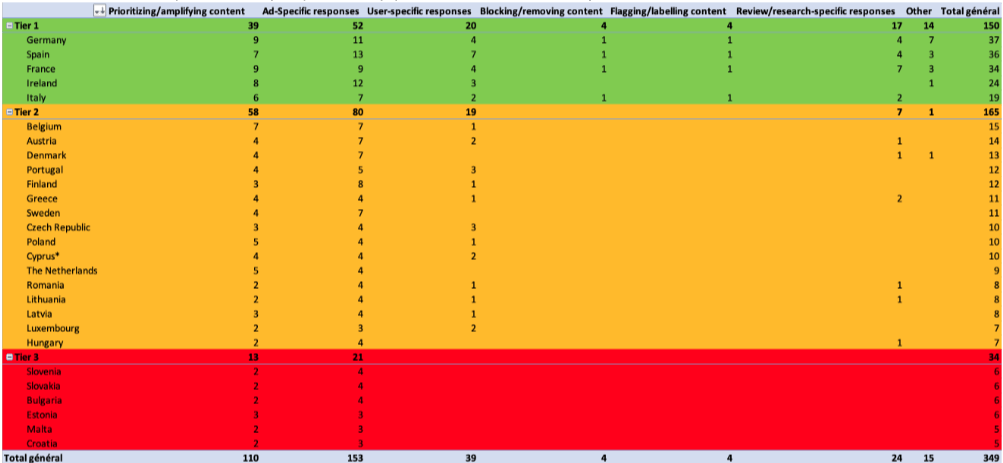

To measure the country-level responses, we gathered all actions identified in the reports and tagged them according to policy type (content, account, user, review/research, other). The following table lists the number of actions per country reported by platforms in these reports.

type

Based on this analysis, we can clearly identify three groups of EU countries labeled with colours:

- Tier 1 countries (in green) benefit from both a good mix of policy actions and a high number of specific country responses (at least 19 responses reported from platforms)

- Tier 2 countries (in orange) have a limited policy mix which does not include any blocking/removing content, nor flagging or labelling.

- Tier 3 countries (in red) have both a poor policy mix and a very low level of country-specific responses.

It is noteworthy that Tier 1 countries are composed of the biggest 4 EU countries in terms of population, plus Ireland. (In addition to being the EU headquarters to many tech platforms, Ireland is the largest English-speaking country left in the EU after Brexit.) Germany, at the very top of our ranking has had its own national social media regulation, the NetzDG, since 2018. Concerns over differentiation from platforms based on languages have recently been voiced by civil society and even in the European Parliament INGE Committee on Disinformation3. Meanwhile in the United States, a coalition of media advocacy groups, civil rights organisations and lawmakers came together in March to call on Facebook to take accountability for Spanish language misinformation.

Regarding Tier 3 countries, the disinformation responses provided by platforms are for a vast majority common to all EU member states, reflecting how few country-specific efforts have been reported.

relation to their population. In other words, this shows reported platform action related to market size.

Platforms make no mention of 1/3 of EU member states when reporting on media literacy campaigns. 9 out of 27 member states are absent in the media literacy reporting: Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Malta, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden.

Platforms pay even less attention to granular data when it comes to fact-checking and research partnerships. 17 out of the 27 member states are not mentioned with regards to fact-checking: Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden.

Striking in our view as well is where platform funding for fact-checking and disinformation research has reportedly ended up. Based on the monthly reports, only 8 EU member states have benefited from platform funding: Denmark (1 grant), France (4 grants), Germany (3 grants), Greece (2 grants), Hungary (1 grant), Italy (1 grant), Lithuania (1 grant), Spain (3 grants).

- Between August 2020 and March 2021, Facebook reported on funding to disinformation research and fact-checking organisations in 8 EU member states (Denmark, France 3 grants; Germany; Greece 2 grants; Hungary; Italy; Lithuania; Spain 2 grants).

- Important to note is Facebook’s partnership with the European Journalism Centre, which is distributing $3M through the European Journalism COVID-19 Support Fund. However there are no country-level details included in the COVID-19 disinformation monthly reports.

- In August 2020, Google reported on funding for fact-checking and verification efforts through the Google News Initiative, with grantees in 3 member states (France, Germany and Spain).

- Google also mentioned the Global Journalism Emergency Relief Fund through Google News Initiative, which in EMEA provided funding to 1.550+ recipients from a global total of 5.300; and a $3M COVID-19 vaccine counter-misinformation open fund, but no country-level details are included in the COVID-19 disinformation monthly reports.

- TikTok does not report whether they have provided fact-checking or research grants.

- Twitter only mentions one donation to a fact-checking organisation in Germany.

Conclusion

- The platforms’ monthly reports are annoyingly diverse and difficult to compare. More detailed guidelines on common metrics and streamlined reporting is needed to allow for meaningful comparison of platform responses.

- Each platform has their own reporting style and fills in the metrics according to their preferences. Our analysis focused on types of policy actions where some level of comparison was possible, but repeatedly we had to note that some platforms simply hadn’t adopted a particular metric in their reporting. We also noted that a large part of these reports is identical every month, which does not facilitate the analysis of the actions reported.

- In our view, country-level and actor-specific reporting on beneficiaries of advertising credits and disinformation research/fact-checking funds, as well as on media literacy and fact-checking partnerships would already provide a much richer picture of actions taken across EU member states.

- In addition, though platforms report extensively on more invasive responses (flagging & labelling, blocking & removing, limiting & demoting, account-specific), country-level reporting on these policy actions is very sparse and ad hoc. Based on the partial information provided, however, it is clear that more granular country-level data could be provided if it were required.

- The self-reporting per country reveals clear inequalities in the amount and mix of platform policy actions between EU member states. New platform actions should urgently focus on small and Eastern European member states.

- Our analysis of the monthly reports reveals that a top tier of five countries (Germany, France, Spain, Ireland and Italy) benefit from granular reporting and a balanced mix of policy actions. These countries are the usual suspects: they have large population sizes, English-speaking communities, or existing regulatory power.

- Based on the reports, small and Eastern European member states are largely ignored. As highlighted in our previous reporting on disinformation in Bulgaria, we ask for a coherent approach in Europe. It is not possible that some European populations are treated as second-class citizens because of a lack of policies from platforms.

Action points

In its strengthened form, the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation should require, at a minimum:

- More harmonisation in reporting. While there are multiple ways to report data, and reports need not be identical, the current situation is not tenable for researchers and civil society organisations seeking to compare data across platforms or simply to track developments on one platform over time. Reporting should clearly highlight updates in order to facilitate analysis.

- Signatories to provide country-specific metrics related to the audience of disinformation (reach), engagement (clickthrough rate, etc.), funding of in-country fact-checking or research activities, and indicators of the prevalence and strength of in-country civil society relationships.

- Signatories to establish a register of beneficiaries of ad-credits detailing amounts granted, spent, as well as report on the impact of these policies.

1. Reports on March actions were released after we finished this analysis and are available here: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/reports-march-actions-fighting-covid-19-disinformation-monitoring-programme

2. As with our previous analysis we do not look at all the signatories, but at the major platforms (Google, Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok).

3. During the joint INGE-AIDA Committee meeting on April 15, 2021, the Committee rapporteur Sandra Kalniete raised this issue in a question, evoking EU DisinfoLab’s recent work on Bulgaria.