by Raquel Miguel Serrano, Roman Adamczyk, Maria Giovanna Sessa, and Laurem Hamm

This blog post is part of a series on Covid-19. Please have a look at our dedicated hub and subscribe to our mailing list of updates.

If you have spotted similar narratives or strategies, please help us to update this document by reaching out to us at info@disinfo.eu

Click here for an update on the latest trends from April

As the virus swept across the world, we decided to zoom into the narratives defining what the WHO term as “the infodemic”. Based on our monitoring of independently fact-checked disinformation from France, Italy, and Spain, we have been able to draw trends from the content, such as the strategies and platforms used to disinform. We have analysed the time period from the end of January to the last week of March and accordingly noticed an evolution in the disinformation.

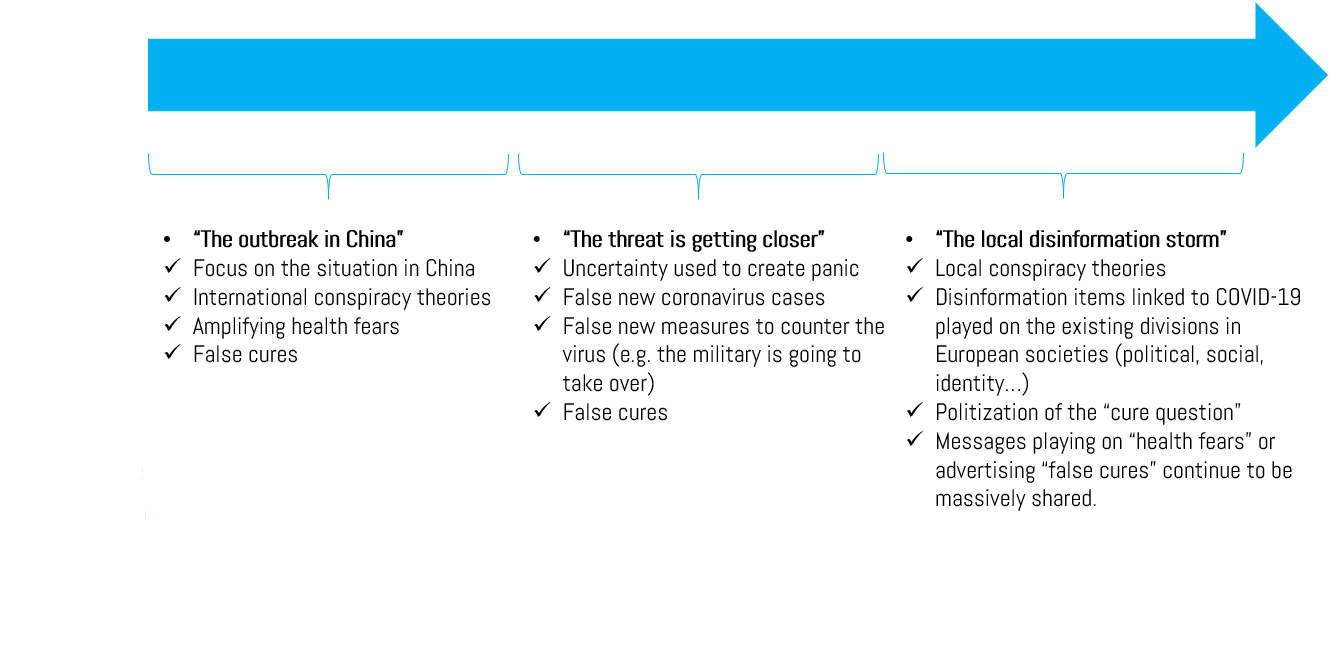

The evolution of Covid-19 disinformation

According to our observations, the evolution of Covid-19 disinformation in France, Italy, and Spain reflected the physical spread of the virus across the world. In the beginning, disinformation centred on the outbreak of Covid-19 in China, and once the virus started to globally diffuse, there, too, was a shift in the narratives. Suddenly, disinformation focused on fear and panic in light of the anticipated arrival of the virus. Once the virus hit Europe and the lockdown measures were slowly implemented, disinformation underwent a process of localisation and became culturally tailored in which Covid-19 narratives reflected important debates in each society.

Typology of narratives

Among the narratives observed, we were able to extract overarching trends for the European countries:

- Health fears;

- Conspiracy theories;

- Lockdown fears;

- False cures, and

- Identity, societal, and political polarisation.

Health fears

The disinformation within this category aimed to deepen fear and panic in society over the virus. In order to do so, disinformation was often accompanied by communication mediums that conferred credibility to the disinformation item. For instance, many decontextualised photos and videos, falsely showing the extent of the virus in China, made their way through the landscapes of all three countries.

In France, for example, a video appeared falsely depicting the corpses of Chinese people on the streets of Shenzhen. While, AFP fact-checked a photo supposedly showing bodies laying on the streets on Wuhan, which in fact was a 2014 photo of people participating in an art project in Frankfurt. This image had circulated in many countries across the world, including Spain (see below).

It has been noted how decontexualised photos are a powerful form of misinformation. In view of this, Lisa Fazio for The Conversation writes that “individuals are more likely to believe the information as we’re used to photographs being used for photojournalism and serving as proof that an event happened”. What’s more, “seeing a photograph can help you more quickly retrieve related information from memory. People tend to use this ease of retrieval as a signal that information is true”.

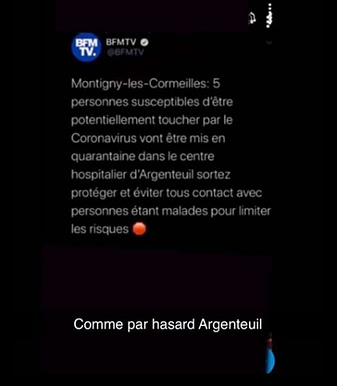

Health fears disinformation heavily used the strategy of impersonating media or authorities via fake screenshots, documents, and notifications to announce new cases and/or health advice. In this way,

- a screenshot surfaced showing French news agency BFM TV reportedly announcing new cases of Covid-19, which turned out to be fake.

- Meanwhile in Italy, leading wire service Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (ANSA) had apparently sent a WhatsApp announcement to Italian citizens, notifying them of the first Covid-19 case in Italy.

- Additionally, a false WHO infographic emerged in Spain, advising citizens to not have unprotected sex with animals.

There was also a mass of alarmist messages, some of which were falsely attributed to real doctors and nurses. These collectively revealed “what’s really going on behind the scenes” vis à vis the virus’ spread to the local context. For instance,

- a WhatsApp audio clip surfaced in Italy of a nurse who claimed that there were serious cases in Aprilia, when in fact none had been recorded.

- Around the same time in Spain, disinformation also centred on announcing false positives, thus adding to the anxiety experienced by society.

Conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories pervaded the disinformation landscape during the period observed. Interestingly, we observed a phenomenon we coin as the “globalisation of disinformation,” which concerns disinformation that knows no borders, which eventually makes its way to several countries in various forms. In this context, the conspiracy theory that Bill Gates had invented the virus, in cooperation with the UK Pirbright Institute, found itself in France, Spain, and Italy. What is intriguing is that, in some cases, conspiracy theories underwent a process of localisation to suit the cultural context. To illustrate this, in France, one individual claimed that the Institut Pasteur in Paris had created the virus to sell vaccines, which is a hoax that follows the same pattern as the UK Pirbright Institute one.

Other conspiracy theories centred on questioning the source of the virus. In this way, the Covid-19 outbreak was branded as a big pharma plot or a bioweapon unleashed on the world. Another interesting conspiracy theory circulated in Italy and France, which affirmed that Covid-19 is a cover-up for NATO military exercises.

Generally speaking, as affirmed by Northumbria University researchers, “conspiracy theories bloom in periods of uncertainty and threat, where we seek to make sense of a chaotic world”. Therefore, the emergence of conspiracy theories in response to the outbreak of Covid-19 is not so much a surprise.

False cures and advice

With the natural urge to find solutions to existential problems, it is perhaps unsurprising that disinformation centred on spreading false cures. This kind of disinformation was predominantly spread via messaging apps and sometimes involved the impersonation of health professionals. To illustrate this, a WhatsApp message surfaced in Italy reportedly sent by a Professor Pascale from the IRCCS Galeazzi Orthopedic Institute who warned that those suspected to have Covid-19 shouldn’t take anti-inflammatory medication. In reality, this individual had never sent such a message and the evidence to support this thesis isn’t reliable enough at present. Moreover, this belief also found popularity on WhatsApp chats in Germany, Austria, Slovakia, and France (see below). Other cures communicated via WhatsApp included the claim that taking vitamin C or gargling salt water can cure Covid-19. In addition, AFP Factuel has even dedicated a whole page to debunking false cures.

WhatsApp seemed to be an important conduit for Covid-19 mis/disinformation; it was able to spread with relative ease on WhatsApp, as individuals generally tend to trust the source of information greatly. WhatsApp’s role in the dissemination of Covid-19 misinformation is well documented, but assessing the virality of mis/disinformation on the platform is near impossible due to the opacity of WhatsApp.

Lockdown fears

As the lockdown loomed in France, Spain, and Italy, many disinformation items were spread via a strategy of attributing the (dis)information to an authoritative figure. In general, this disinformation announced false government measures in response to Covid-19, thus stimulating confusion and often panic among the populations.

- In France, a letter attributed to the Ministry of Education was disseminated, which falsely announced the postponement of the school summer holidays.

- In Italy, some people rushed to supermarkets after the dissemination of some disinformation items that claimed supermarkets would close for 10 days.

- In Spain, disinformation items about potential shortages and looting in supermarkets were also widely spread.

Moreover, some disinformation sowed further anguish and government scepticism by suggesting a military intervention.

- In Italy, a decontextualised image reportedly depicting military tanks on a freight train in Naples was used to suggest that the government was “hiding something” from citizens.

- In France, one disinformation item (among others) also used a decontexualised image to suggest that military tanks were making their way into Paris to manage the containment of people.

Identity, societal, and political polarisation

With the mass outbreak of Covid-19 in France, Spain, and Italy, we observed a shift in the strategy behind the disinformation. Disinformation has been increasingly designed to, both implicitly and explicitly, inflame the divisions in European countries, whether this concerns identity, societal, or political cleavages. For example, Spanish socialist Minister of Education Isabel Celaá had reportedly worn a purple glove over “fear of the coronavirus” at an 8M demonstration, which was actually worn to mark the International Women’s Day demonstrations.

As France went into lockdown, a decontextualised video emerged showing young men from minority backgrounds brawling in a Lidl supermarket. This video was reposted by the Facebook page of the far-right Rassemblement National Saint Denis branch, illustrating how such disinformation can be used to aggravate identity and political cleavages.

In Italy, the migration debate intertwined with Covid-19, with disinformation examples such as:

- a doctor who confessed that the government prevents them from testing migrants in reception centres, or

- the claim that Nigeria had witnessed the first case of Covid-19.

Needless to say, the objective of this disinformation was to deepen political polarisation.

Concluding thoughts

In summary, there are four strategies that reappeared throughout our monitoring of the disinformation present in Italy, France, Spain, which are worth recapping on:

- The impersonation of authoritative figures to confer credibility and legitimacy to the disinformation.

- The use of WhatsApp in all three countries to accelerate the spread of inaccurate information.

- The mass use of decontexualised images and videos to sow panic and confer credibility to the disinformation.

- The significance of anonymous channels on Telegram that share information linked to the COVID-19, which is then repropagated on mainstream platforms.

Our experience of monitoring the disinformation landscapes across Europe shows that, alongside the news cycle, there has been a complete reorientation of the disinformation ecosystem towards the coronavirus, whether that concerns deceptive social media accounts or clickbait websites. In light of the latter, our recent investigation on Africa24 – an Africa-based network that built clickbait health scams for profit – shows how disinformation actors are capitalising on the outbreak to profit via coronavirus-themed clickbait.