By Nicolas Hénin, EU DisinfoLab External Researcher

Introduction

From the meddling of the Russian Intelligence Research Agency (IRA) in the 2016 US elections to a hack and leak operation targeting Emmanuel Macron, whose design and timing showed a determination to disrupt the election, several spectacular attempts at electoral interference have made the headlines in recent years. On the heels of the German federal election and in the lead-up to the French presidential election, in an era where disinformation has become a common political strategy, this research focuses on verified cases of foreign interference during elections that involved disinformation.

This overview first offers definitions and frameworks for key topics. It then turns to the main tactics, and more especially, the recent trends. Specific suggestions for improving resilience to foreign election interference are beyond the scope of this overview, which seeks primarily to improve understanding of the challenge.

Definitions

Disinformation can be defined in terms of manipulative, deceptive or harmful actors, behaviours and content, manifesting in a variety of forms that can also be applied to the electoral context. The manipulations may consist of false behaviours, like the amplification of a political message through bots or trolls on social media, or the prompting of real-life events, like demonstrations, in a city where opposite sides are likely to scuffle. They can also rely on false content, like lies promoting one candidate, denigrating another, or undermining confidence in the electoral process.

Deceptions may also relate to who the messengers (actors) truly are, even if the content of the message itself may be factually correct. In this regard, it may be difficult to differentiate foreign from domestic electoral disinformation. In fact, some strategies are good at blurring the lines, for instance when foreign actors hire domestic proxies. A further challenge to our theoretical framework, information manipulation will usually mix different aspects, including disinformation alongside more subtle manipulative tactics.

Therefore, the expression “foreign electoral interference” can cover very different realities, whose degree of harm varies consistently. For the sake of this analysis, we are exclusively going to focus on interferences that relied on some form of false or deceptive information. In view of this, definitions of the phenomenon that emerge from existing research are mainly based on:

The perpetrators of the interference

A distinction is commonly made between state and non-state actors. As for the latter, a further nuance should be introduced between truly non-state actors and actors that could be described as “sub-state” or “para-state”, namely that are not structurally dependent on a state but have interests very close to those of the state, and are either associated with it or act as its proxy. In this category fall the electoral interference attempt of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in the US 2020 elections, and the clandestine operations conducted by Yevgeny Prigozhin.

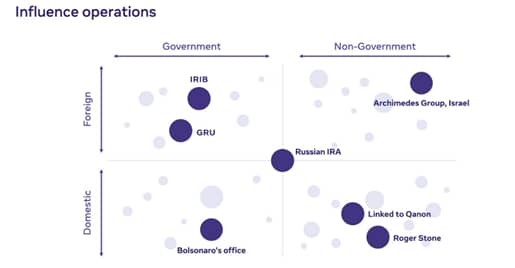

Though this overview is focused on foreign electoral interference, it should be recalled that not all electoral interferences come from abroad. In the latest report published by Facebook on assets taken down for coordinated inauthentic behaviour (CIB), many concern political disinformation around “highly-targeted civic events like elections” that often originate in the target country, suggesting that election disinformation in the 2020 US Presidential election was broadly a domestic issue. In view of this, the platform categorises influence operations in a double-entry table that considers government as well as non-government actors, and foreign as well as domestic targets. Given the relevance of elections in influence operations, a similar classification can also be applied to election interference.

The visibility of the interference

A good standard to assess the degree of publicity of foreign electoral interferences is offered by the Australian Department of Home Affairs, which considers “foreign influence” and “foreign interference”. The former consists of open and transparent activities conducted by governments to influence certain matters. An example is President Erdogan’s call for German citizens of Turkish descent not to vote for the coalition led by chancellor Merkel during the 2017 parliamentary election, while labelling Germany’s three main political parties as “enemies of Turkey”.

Foreign interference on the other hand includes “activities going beyond routine diplomatic influence practised by governments, that may take place in isolation or alongside espionage activities” (European Parliament, 2020). This definition draws a line between some visible soft power strategies, e.g. making openly supportive partisan statements, and interference, e.g. tampering with the authenticity of the democratic debate, relying on hidden actors or proxies, behaving in an inauthentic manner, and propagating doctored or fabricated material. A 2019 European Parliament resolution framed the notion of foreign interference in elections as part of a broader strategy of hybrid warfare that affects the right of citizens to participate in the formation of a government. Therefore, this is a complex, multi-stakeholder issue that should be addressed through the frames of counter-disinformation, security, and foreign policy.

The objectives of the interference

Foreign interference in democratic processes, of which elections are the fundamental characteristic, can serve various goals: from the achievement of a certain preferred outcome to a more general aim to increase polarisation, breach information security, and ultimately undermine democratic institutions.

The US National Intelligence Council differentiated between “election influence”, including overt and covert activities to affect the outcome of an election, and “election interference”, as a subset of election influence operations that is limited to the technical aspects of the voting process. Such a distinction tries to separate physical hostile actions, like the hacking of a candidate’s campaign, a supervision body or the voting system itself, from actions that are limited to the field of perceptions (i.e. aimed at influencing the voter’s choice). However, the effects of these attacks often overlap: tampering with an information system can potentially affect voters’ confidence in the voting process. Four days before the 2014 Ukrainian election, pro-Russian hacktivist group CyberBerkut (with suspected ties to the GRU) compromised the country’s central election system by deleting critical files and rendering the vote-tallying system inoperable. Three days before the vote, CyberBerkut released exfiltrated data online as proof of the operation’s success. The attack was later described by the Ukrainian Central Election Commission as “just one component in an information war being conducted against our state”. Despite the limited impact of the attack, since the system was restored using backups, the Russian media exploited the event to label electoral results as erroneous.

The impact of the interference

The actual impact of an interference is usually challenging to assess. Looking at the interventions in third countries by USSR and the USA during the Cold war, Dov H. Levin (2016) showed that interventions by global powers “usually significantly increase the electoral chances of the aided candidate”, and that “overt interventions are more effective than covert interventions”.

The perception of the interference by voters is a key indicator of impact. It is especially interesting when several competing foreign influence operations target an election. To provide an example, Shulman & Bloom (2011) studied the Ukrainian people’s reaction to Western and Russian intervention in the 2004 presidential elections (the so-called Orange Revolution). They found that the average Ukrainian did not welcome efforts by Western governments, international organisations, and non-governmental organisations to shape their country’s electoral landscape, while electoral interference conducted by Russia was perceived less negatively, perhaps due to the shared Slavic identity. It is noteworthy that even some highly sophisticated or ambitious operations may fail and ultimately have only a marginal influence on the outcome of the election.

Main tactics

Influence operations (IOs), i.e. coordinated efforts to manipulate or breach public debate for a strategic goal, rely on a plurality of tactics that draw upon deceptive content as well as deceptive behaviours. In view of this, we now delve into a number of these strategies:

- Micro-targeting is a marketing strategy that employs users’ data to segment them into groups for content targeting, and it has been now increasingly extended to voters to address personalised political advertisements. Although this tool is not necessarily illegal, it has also been used for malicious purposes: prior to the 2016 US elections, the IRA used Facebook’s targeted advertising to direct polarising ads on divisive topics such as race-based policing towards vulnerable groups. The Cambridge Analytica scandal is another emblematic example of the range of “micro-targeting” strategies that can be used to try interfering in elections by both foreign and domestic actors.

- Troll armies, whether in the form of live actors behind troll and sock-puppet accounts, bots as their digital counterparts, or with cyborgs – i.e. “a kind of hybrid account that combines a bot’s tirelessness with human subtlety” – there is a spectrum of manual to automated entities and assets that tend to create and amplify controversial content on social media. These strategies entered the US electoral landscape in 2016, as Russia resorted to these online agitators. However, these entities became domestic instruments as well, for instance when conservative-leaning firm Rally Forge posed as a progressive actor to divide Democrats. If troll farms were made popular by Prigozhin’s IRA in Saint Petersburg, they are by far no longer a Russian monopoly, especially since PR and other digital marketing private companies are developing similar disinformation activities. Hundreds of fake assets created by the Israel-based Archimedes Group were banned by Facebook in 2019 following claims by the platform that they were used to influence political discourse and elections in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia.

- Impersonation can take different forms. According to First Draft, imposter content consists of the impersonation of genuine sources. An example in the electoral arena comes from the fake Belgian website LeSoir.info, which spread disinformation ahead of the French 2017 election, pretending to come from presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron. Deepfakes are another form of impersonation, identified as a rising threat which the rapid evolution of technologies makes hard to identify. Deepfakes may be used in the dissemination of fake Kompromat, i.e. the sharing of compromising private material. Easier to make, but also dangerous, another challenge is presented by “cheap fakes”, which simply take authentic content and vary the speed of a video or edit it selectively, e.g. one might remember a slowed down video of Nancy Pelosi that made her seem inebriated.

- Hack and leak is a tactic that falls into the category of malinformation, which is the deliberate publication of private information for personal or corporate rather than public interest. The leaked contents may be authentic, fabricated, doctored or a mix of all these. Recent examples include the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak and the 2017 Macron email leak, which were both amplified by such established actors as WikiLeaks.

- Fuelling polarisation online and offline by exacerbating divisions, based on real or manipulated information, is a tactic used by numerous actors, whether to side with a specific party or candidate or to heighten partisanship. It also coincides with the first two of the five Russian disinformation objectives as identified by Clint Watts: to undermine trust in democratic governance and to exacerbate divisive political fissures. Such a tactic has driven the IRA to use impersonation to falsify support simultaneously for the Black Lives Matter movement and white supremacist narratives during the 2016 US elections campaign. In view of the counterintuitive nature of such a strategy, which can also be considered an objective of the interference, the ultimate goal seems to be to reduce the attractiveness of liberal democracy.

- Manipulation of civic processes undermines the trust in the electoral process per se by fuelling confusion, especially targeting those who are undecided on whom to vote for, leaning toward changing their mind or even unsure whether to go to the polls at all. In this regard, voter suppression is a documented strategy used to influence the result of an election by discouraging or restraining a specific group of people from voting. Most recent examples are domestic, including Republicans targeting Black and Latino communities with electoral disinformation, or various cases suggesting that postal voting is a fraud or will tamper with the election’s result). From a foreign perspective, Iranian actors were found to have impersonated the far-right “Proud Boys” organisation in emails sent to voters in the US. Several takedowns announced by Facebook concern coordinated inauthentic behaviour meddling with election integrity, like Russian and Iranian sets ahead of the 2018 midterms in the US.

Recent trends

Two primary sources provide us with valuable insights into recently deployed operating modes and tactical evolutions: the declassified public version of the National Intelligence Council report Foreign Threats to the 2020 US Federal elections (March 2021), and Facebook’s Threat Report; The State of Influence Operations 2017-2020 (May 2021). The latter for instance notes a clear evolution since its previous report, when it spotted “large numbers of fake accounts and the amplification of hacked and leak operations”.

Their main take-aways are:

- Facebook warns of “perception hacking” as an innovative tactic that weakens trust in democracy by “sowing distrust, division and confusion among the voters it targets”. The tactic is described as a rather small-sized intrusion that triggers an oversized psychological effect once it enters the public debate, giving the idea that certain actors or issues on the agenda are more powerful than they actually are. For instance, the news that Russian and Iranian groups had broken into the US election data system ahead of elections was blown out of proportion, considering that they had simply obtained publicly available information.

- A clear trend is to domesticise and authenticate influence operations. In 2016, US voters were targeted by narratives produced by trolls in Saint Petersburg. In 2019, some Ukrainian Facebook users received offers by Russian agents to sell or rent access to their accounts in order to propagate narratives, bypassing the platform’s countermeasures. The ultimate goal is to recruit or use local and authentic influencers who will bring narratives to the traditional information system (e.g. traditional media, main social networks accounts, prominent individuals, etc.).

The DNI talks about “laundering influence narratives”, a tactic that covers two apparently similar but different realities. On the first hand, information laundering on networks of websites allows disinformation actors to avoid platform moderation, as showed with InfoRos in our previous research. The objective is to develop a strategy to make sure that the content produced by foreign websites is regularly reproduced by local actors. Mechanically, it makes the identification of the initial producer of specific narratives and disinformation more complex. On the other hand, there is an increased use of local actors, ranging from troll farms in Ghana and Nigeria to the Peace Date case. In this regard, Facebook notes an adaptation of behaviours by threat actors in order to hide in the grey area “between authentic and inauthentic engagement and political activity”. It also points out that adaptations to make online influence operations “shift from ‘wholesale’ to ‘retail’ IO”. As they become more targeted on one platform, they also lose effectiveness when they are diluted across a number of platforms. This is yet another trend that blurs the boundary between domestic and foreign elections interference.

- Disinformation for hire. Similar to other interference operations, election interference may be increasingly offered as a service, just like cybercriminals offer their hacking to an actor, providing to it an extra layer of operational security and deniability. Such services may be proposed by actors working on the verge of legality as well as by well-established PR or digital marketing companies. “Disinformation for hire” was blatantly exposed when Fazze was tasked to denigrate Covid-19 vaccines. According to the DFRLab, such companies are blooming in the political landscape and, as Stanford Internet Observatory revealed on US-based strategic communications firm CLS Strategies, they also meddle in elections. In August 2020, Facebook took down a network of 55 Facebook accounts, 42 Pages and 36 Instagram accounts attributed to it that engaged in coordinated inauthentic behaviours targeting contested elections in Bolivia and Venezuela.

Conclusions

- Our research explored the main definitions of electoral interference, a phenomenon that is difficult to grasp due to its cross-dimensionality as it regards security, democracy, foreign affairs, and disinformation.

- An overview of the key topics and tactics, with case studies from recent years, was provided, focusing on foreign interference – although at times we inevitably delved into domestic patterns of interference as well.

- Foreign interference draws on diverse strategies to attack specific groups and candidates. In particular, elections are highly targeted events as the epitome of our democracies. Therefore, an underlying goal of these inferences is to fuel polarisation, either directly by manipulating the process or indirectly by instilling doubt in the population.

- Foreign election interference is getting more and more complex. For example, some actors regularly use local proxies and digital marketing companies as intermediaries to hide their tracks.

- Overall, it is difficult to assess the precise impact of electoral interference though there is well-founded concern about its disruptive role in the functioning of democracy. Hence, it is crucial that platforms, civil society actors and governments work in harmony to defend the integrity of the voting process.