By Trisha Meyer and Clara Hanot

This blogpost

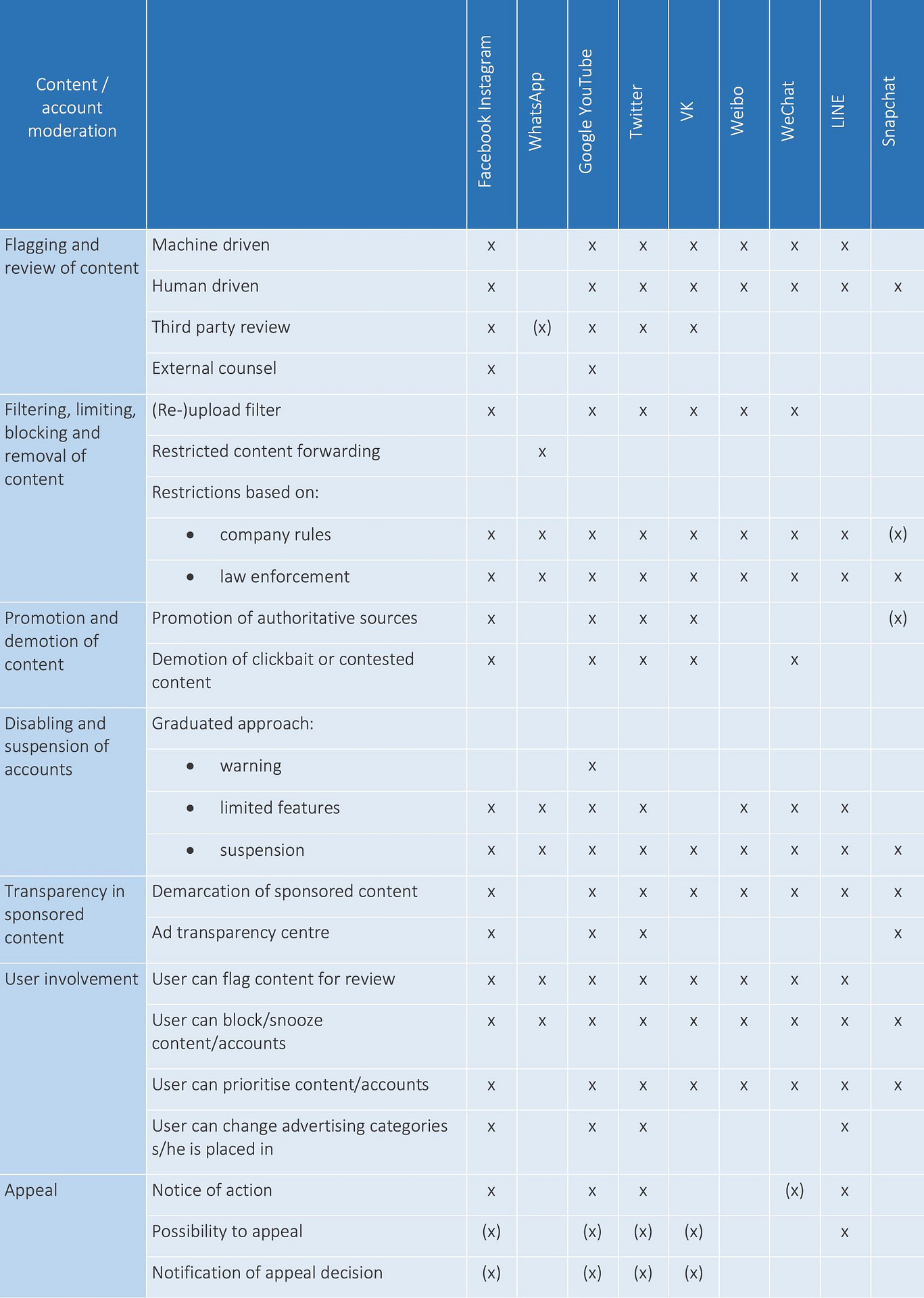

- compares how 11 global internet communications companies address disinformation through 7 forms of content and account moderation;

- presents a case study on additional measures taken by Facebook/Instagram, Twitter and Google/YouTube during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- argues that internet communication companies are acting as definers, judges and enforcers of freedom of expression on their services;

- concludes that platforms’ responses to the ‘disinfodemic’, in particular the further automation of curation, confirm once again the urgent need for transparent and accountable content moderation policies.

Internet communication companies are simultaneously under pressure to tackle disinformation on their networks, as questions are raised regarding the shift to private regulatory action, in which public scrutiny is almost entirely absent.

In the recently published UNESCO/ITU Broadband Commission research report on Balancing Act: Countering Digital Disinformation While Respecting Freedom of Expression, we examined how 11 geographically diverse and global internet communications companies that enjoy a large user base expressly or indirectly address the problem of disinformation through content curation or moderation. These responses are primarily outlined in the companies’ terms of service, community guidelines and editorial policies.

As we completed the first round of our analysis in February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was gaining in intensity. During the past months there have been unprecedented reactions from internet communications companies to limit the ‘disinfodemic’ of false health-related information and redirect users to authoritative sources. In July 2020, we repeated our exercise for Facebook/Instagram, Google/YouTube and Twitter to take into account platform responses during the pandemic.

At both stages of our research (February and July 2020), we paid special attention to how decisions on content moderation are made, whether and how users or third parties are enlisted to help with content monitoring, and which appeal mechanisms are available. Although taking a close look at platform policies does not necessarily correspond with platform practices, it allows us to evaluate whether companies are living up to their own standards and to compare measures across time and between platforms. Whether and where the internet communications companies strike the balance between protection and empowerment in their policies sets the tone for our online experience.

In this blogpost, we provide insight into the curatorial responses to harmful content and disinformation outlined in internet communications companies’ terms of service, community guidelines and editorial policies, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent measures have included promotion of authoritative sources, alongside an increase in automation of content moderation with (even) less guarantee of review and appeal. Pen America recently published an amazing searchable dataset of actions and announcements made by the biggest 13 internet communications companies during the first six months of 2020.

- Flagging and review of content

Potentially abusive or illegal content on online communication platforms can be flagged through automated machine learning, and manually by users and third party organisations (such as law enforcement, fact-checking organisations, and news organisations operating in partnership). Automated detection is on the rise and is important to tackle concerted efforts of spreading disinformation, along with other types of communications deemed potentially harmful. To illustrate the automation of content moderation, over the period from April to June 2020, a total of 11,401,696 videos were removed from YouTube. Of these, only 552,062 (or 4.84%) were reported by humans.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, most of these companies moved towards heavy use of automation for content curation. To limit the spread of COVID-19, internet communications companies and government authorities encouraged confinement of workers at home. With a large number of staff working remotely, the companies chose to increasingly rely on algorithms for content moderation. This has been the case for Facebook/Instagram, but also Twitter and Google/YouTube. As anticipated by the companies, the increase in automated moderation led to bugs and false positives.

- Filtering, limiting, blocking or removal of content

After receiving machine or human-driven notifications of potentially objectionable material, internet communications companies remove, block, or restrict content, applying a scale of action depending on the violation at hand. It can be noted that the companies’ rules can be more restrictive than their legal basis in a number of jurisdictions. A good example is Twitter’s decision to ban paid political advertising globally in November 2019. At the other end of the spectrum, Facebook continues to run categories of political advertising without fact-checking their content and has also resisted calls to prevent micro-targeting connected to it. In September 2020, they made slight restrictions in banning new political ads in the week before the US presidential elections.

To limit the dissemination of disinformation narratives related to COVID-19, several companies have taken a more proactive approach to removing content. Google proactively removes disinformation from its services, including YouTube and Google Maps. For example, YouTube removes videos that promote medically unproven cures. Facebook committed to removing “claims related to false cures or prevention methods — like drinking bleach cures the coronavirus — or claims that create confusion about health resources that are available”. Also, the company committed to removing hashtags used to spread disinformation on Instagram. Twitter broadened the definition of harms on the platform to address content that counters guidance from public health officials.

- Promotion/demotion of content

Another option to tackle disinformation is based, to quote DiResta, on the assumption that “freedom of speech is not freedom of reach”, whereby sources deemed to be trustworthy / authoritative according to certain criteria are promoted via the algorithms, whereas content detected as being disinformational (or hateful or potentially harmful in other ways) can be demoted from feeds. As an example, on Facebook, clickbait content is tackled by reducing the prominence of content that carries a headline which “withholds information or if it exaggerates information separately”. Facebook also commits to reducing the visibility of articles that have been fact-checked by partner organisations and found wanting, and the company adds context by placing fact-checked articles underneath certain occurrences of disinformation.

The primary strategy of the internet communications companies to face disinformation related to COVID-19 has been to redirect users to information from authoritative sources, in particular via search features of the companies’ platforms, and to promote authoritative content on homepages, and through dedicated panels. On Facebook and Instagram, searches on coronavirus hashtags surface educational pop-ups and redirect to information from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and local health authorities. Google also highlights content from authoritative sources when people search for information on coronavirus, as well as information panels to add additional context. On YouTube, videos from public health agencies appear on the homepage. Twitter, meanwhile, curates a COVID-19 event page displaying the latest information from trusted sources to appear on top of the timeline. Finally, several platforms also granted the WHO and other organisations free advertising credit to run informational and educational campaigns.

- Disabling or removal of accounts

In addition to curating content, internet communications companies tackle what they call coordinated inauthentic behaviour’ at an account level. Online disinformation can be easily spread through accounts that have been compromised or set up, often in bulk, for the purpose of manipulation. Several companies prohibit ‘coordinated inauthentic behaviour’ (including interference from foreign governments) in their terms of service agreements. For instance, WhatsApp “banned over two million accounts per month for bulk or automated behavior” in a three-month period in 2019. Roughly 20% of these accounts were banned at registration.

It does not appear that Facebook/Instagram, Twitter or Google/YouTube have implemented additional measures regarding the disabling and suspension of accounts with regards to COVID-19 disinformation. Nonetheless, Twitter has worked on verifying accounts with email addresses from health institutions to signal reliable information on the topic.

- Transparency

Content moderation can interfere with an individual’s right to freedom of expression. Even though private actors have a right (within legal boundaries) to decide on the moderation policies on their services, an individual’s right to due process remains. Insight/transparency should also be given to users and third parties into the process of how decisions are made, in order to guarantee that these are taken on fair and/or legal grounds.

In 2018, a group of US academics and digital rights advocates concerned with free speech in online content moderation developed the Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation (a consultation to update the principles is ongoing). These principles set the bar high for the companies, suggesting detailed standards for transparency reporting, notice and appeal mechanisms. Indeed, as a de facto public sphere, there is a need for dominant entities to use international standards, and not operate more limited ones.

Facebook/Instagram, Google/YouTube, Twitter, Snapchat and LINE provide periodic (e.g. quarterly) public transparency reports on their content moderation practices as they align with external (legal) requirements. They tend to be less transparent about their internal processes and practices. All except LINE also run (political) advertising libraries. The libraries of Facebook and Twitter cover all advertisements globally, while Google provides reports for political adverts in the European Union, the UK, New Zealand, India and the United States, and Snapchat covers political adverts in the US. In several jurisdictions (Argentina, Canada, the EU, France and India) online services (and election candidates) are obliged to provide transparency in political advertising, with many others considering such policy measures.

During the past months, internet communications companies have communicated extensively on their efforts to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Facebook, Twitter and Google have collected and structured their policy actions and announcements in repositories. Public transparency reports have also continued to be published. In May 2020, Facebook announced the members of its long anticipated Oversight Board, which will provide “independent judgment over some of the most difficult and significant content decisions”.

- User empowerment

User empowerment requires control of the content, accounts and advertising they see. Internet communications companies offer varying types of involvement, including flagging content for review, prioritising, snoozing/muting and blocking content and accounts, and changing the advertising categories users are placed in. This last tool is only offered by a handful of platforms. Facebook allows users to update their ad preferences by changing their areas of interest, as relevant to the advertisers who use this information, and targeting parameters. On LINE, users can select their preference for sponsored content on banner adverts on LINE Talk, but not on sponsored content on the LINE timeline or other services.

Related to COVID-19, internet communications companies heavily emphasise prioritising authoritative content (as mentioned under point 4) and have created information centers to help people find reliable information. Search functionalities have also been altered, such as Twitter‘s COVID search prompts and tabs. Facebook has enabled people to request or offer help in their communities, while Google found itself playing a key role in getting educational communities online.

- Appeal mechanisms

Finally, in response to curatorial action taken and in line with the Santa Clara Principles, it is important from the perspective of protecting freedom of expression that companies have in place procedures to appeal the blocking, demotion or removal of content, disabling or suspension of accounts. This entails a detailed notification of the action, a straightforward option to appeal within the company’s own service, and a notification of the appeal decision.

As is evident from the table, there is quite some variance in the social media companies’ approaches to appeals. Although external appeal to an arbitration or judicial body is theoretically possible in some countries, especially where disinformation intersects with a local legal restriction, few companies offer robust appeal mechanisms that apply across content and accounts, or to notifying the user when action is taken.

No specific changes to appeal mechanisms related to COVID-19 have been noted, although Facebook cautioned that more mistakes were likely and that it could no longer guarantee a human-based review process. Similar announcements were made by other companies. As Posetti and Bontcheva explain, in cases where automation errs (e.g. a user post linking to a legitimate COVID-19 news or websites were removed), the dilution of the right to appeal, and the lack of a robust correction mechanism represent potential harm for the users’ freedom of expression rights.

Previous disinformation campaigns have made clear that without curatorial intervention, the services operated by internet communications companies would become very difficult to navigate and use due to floods of spam, abusive and illegal content, and unverified users. As the companies themselves have access to data on their users, they are well placed to monitor and moderate content according to their policies and technologies. Putting strategies in place, such as banning ‘coordinated inauthentic behaviour’ or promoting verified content, can help limit the spread of false and misleading content, and associated abusive behaviours. However, policies are best developed through multi-stakeholder processes, and implementation thereof needs to be done consistently and transparently. Monitoring this could also be aided by more access to company data for ethically-compliant researchers.

It is difficult to monitor and evaluate the efficacy of curatorial responses in the absence of greater disclosure by the internet communications companies. This has led to growing controversy over the companies identifying, downgrading and deleting content and accounts that publish and distribute disinformation. Some review and moderation is machine-driven, based on scanning hash databases and patterns of inauthentic behaviour. But it is unclear which safeguards are in place to prevent the over-restricting of content and accounts. This is borne out via controversies connected to inappropriate deletions justified on the grounds of breaching platform rules. Curatorial responses, especially when automated, can lead to many false positives/negatives.

Redress actions can be taken on the basis of existing law and community standards. Yet, a major limitation in the compliance of social media companies with national regulation needs to be noted, as they operate globally and do not necessarily fall into the legal frameworks of the jurisdictions where they operate. Companies prefer to operate at scale in terms of law: they are usually legally based in one jurisdiction, but their users cross jurisdictions. Adherence to national laws is uneven, and in some cases, moderation policies and standards follow the headquarters’ interpretation of standards for freedom of expression, more closely than a particular national dispensation. In some cases, this benefits users such as those in jurisdictions with restrictions that fall below international standards of what speech enjoys protection.

At the same time, terms of service, community guidelines and editorial policies tend to be more restrictive, and thus limit speech, beyond what is legally required, at least in the jurisdiction of legal registration. Private companies with global reach are thus largely determining, in an uncoordinated manner currently, what is acceptable expression, under their standards’ enforcement. In the absence of harmonised standards and definitions, each company uses its own ‘curatorial yardstick’, with no consistency in enforcement, transparency or appeal across platforms. This results in the internet communication companies acting as definers, judges and enforcers of freedom of expression on their services. Indeed, any move by these companies in terms of review and moderation, transparency, user involvement and appeal can have tremendous implications for freedom of expression. Platforms’ responses to the ‘disinfodemic’, in particular the further automation of curation, confirm once again the need for transparent and accountable content moderation policies.