By Joe McNamee, Senior Policy Expert, EU DisinfoLab

In a world of greys and nuances, there is one near-universal truth – the closer an online intermediary is to an offence, the more effective it can be in helping to bring an end to the offence.

Let’s take three types of disinformation website:

- One that makes money from advertising

- One that uses a misleading domain name

- A network that mimics legitimate news outlets

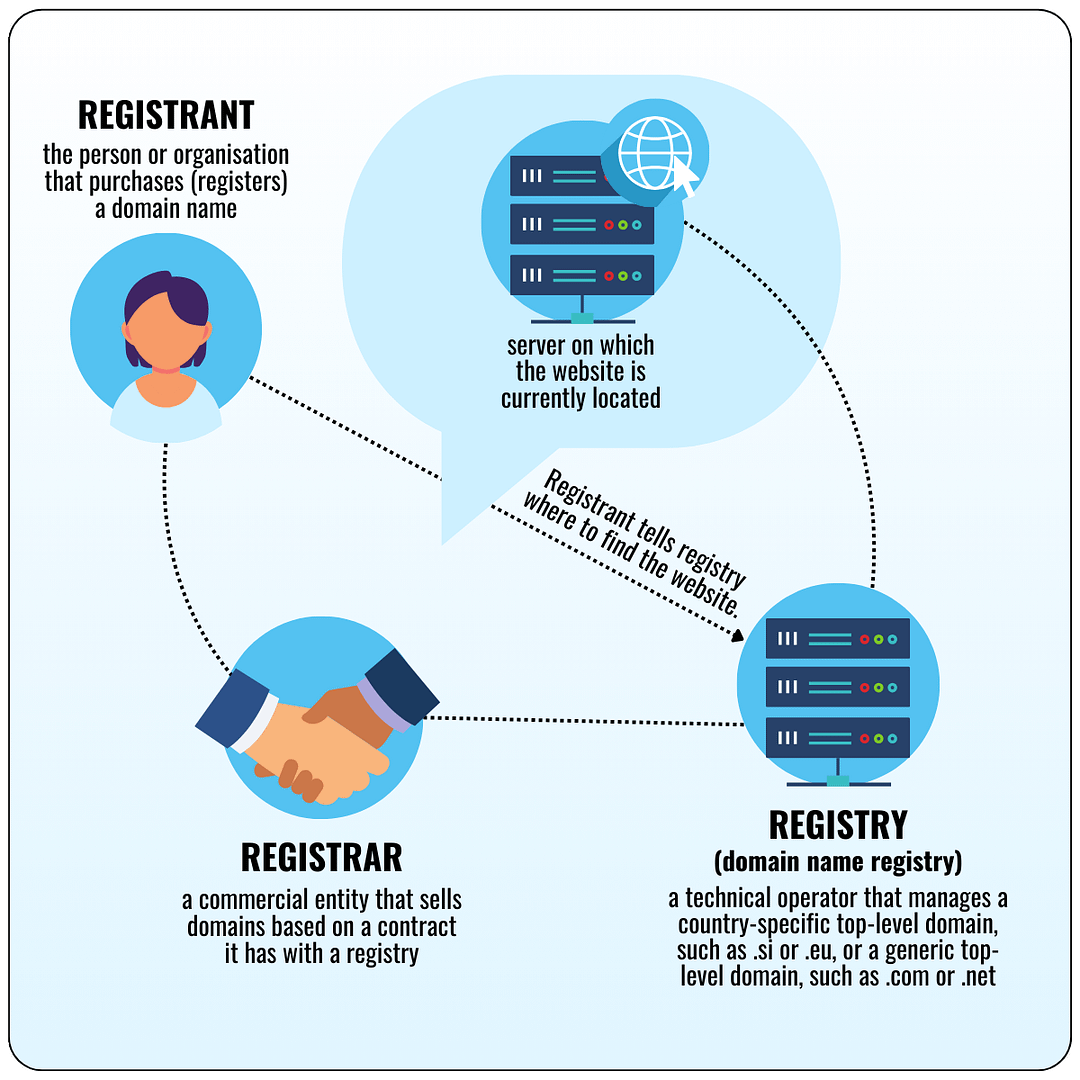

They all use the same basic infrastructure. They buy their domain name (such as disinfo.eu) from a registrar (such as tucows.com), who registers the domain at a registry (such as Eurid.eu). They store their website at a web hosting service (such as virtualroad.org) and configure their domain name to load the website when people access their domain name.

People access the pages using an internet access provider either by putting the domain name in their web browser (like Chrome, Firefox or Edge) or by clicking on a link.

1. One that makes money from advertising

In this famous example, the web domain was entirely legal and the content of the website, while false, was also legal. It would therefore fall far below any usual threshold for action to be taken by the web hosting service, registry, registrar or access providers.

Its primary vulnerability was its business model, because it only existed for advertising. Once Google withdrew ad revenue from the site, its only reason for existing was gone. Smaller ad networks are likely to be less profitable as advertising partners. It should be noted, however, that genuine and well-designed efforts at self-regulation in the online advertising industry are failing.

The solution was the intermediary closest to the actual problem, namely Google. Trying to address such sites via any other intermediary would be ineffective.

2. One that uses a misleading domain name

“Doppelganger” websites use domain names that are confusingly similar to respected news outlets in order to spread disinformation.

We saw above that the owner of a web domain configures it to load its content from a particular web hosting service. So, if the web hosting service withdraws (“takes down”) the website, it can simply be put on another hosting service and be back on line literally in seconds. This process can be easily automated.

On the other hand, the domain name is designed to be confusingly similar to that of a legitimate website, and that is exactly what trademark law prohibits. Revoking the domain name via a complaint to the registry’s dispute resolution procedure is therefore normally possible and undermines the core strategy of this model. Some work has been done to facilitate the creation of a “trusted notifier” model, to allow key stakeholders to have their notices of allegedly abusive domain name registrations processed more efficiently.

One doppelganger site was leparisien.re, which pretended to be the website of the newspaper of Le Parisien, which can be found at leparisien.fr. Le Parisien made a complaint to the registry that runs the .re domain (the French registry operator AFNIC) and the domain leparisien.re was transferred to Le Parisien.

The whole purpose of the website was to have a domain name (and website) that was confusingly similar to the legitimate domain. So, the most effective intermediary to solve the problem was the domain name registry (or registrar, but this opens other questions that are beyond the scope of this short article).

3. A network that mimics legitimate news outlets

Here, the domain name is not confusingly similar to the trademark of a legitimate publication, the content of the site is not illegal, although it may be padded out with content that is copied without authorisation from real news sites.

These sites make up their own legitimate-sounding domain names, use a mix of unauthorised copies of content from other sites and disinformation, and do not use advertising. So, there is no “hook” to use to argue that it would be proportionate for an access provider, website hosting provider, domain name registry or registrar to take any restrictive action.

Using copyright law to require the “takedown” of the website looks like a solution. However, as mentioned in the previous point, the site can be up and running again, possibly in a different jurisdiction, in seconds. Also, when dealing with online harmful or illegal activity, one should always ask – if we do this, what can we expect to happen next? In this case, the logical step would be to replace the copyright-infringing content with AI-generated content, leaving us back where we started.

These sites primarily exist to exploit social media “recommender systems” that organise our news feeds in ways that maximise profits for the social media companies rather than quality, choice and reliability. If these sites are not available via social media, they lose their reason for existing. Social media companies can and sometimes do block links to problematic domains.

However, there is a deeper issue – “recommender systems” are grossly under-regulated, and are frequently blamed for promoting content that is controversial, divisive or dangerous, due to this ostensibly being more profitable for social media companies. Simply telling the companies to “do more” to solve the problems that, arguably, they are causing, can be a faustian deal. Does society believe that a problem can be its own solution? This is all the more dangerous when we realise that it may be the case that no aspect of the content being restricted is illegal. The Guidance Note of the Council of Europe on Content Moderation offers essential safeguards for precisely such situations.

It is also worth remembering that measures to limit virality generated by social media recommender systems will have no effect on unmoderated instant messaging groups.

Similarly, such websites may only exist for other purposes, such as in order to serve as a legitimate-looking “source” for disinformation narratives. In this case, there may be no justification at all for any internet intermediary to take any action. In such circumstances, exposing the deception and the networks behind the sites may be the only realistic action that can be taken to mitigate the harm.

Conclusion

Fighting disinformation on the open web requires ongoing analysis and thoughtful, targeted work by all stakeholders. There is no one model of web disinformation and any “quick fix” solution that claims to be a durable solution in all cases will inevitably disappoint.